A Teetotaler Defends Maryland's Liquor Stores

Unlike the vast majority of the country, grocery stores and other chain retailers aren't allowed to sell alcohol in Maryland. It should stay this way.

The Counterpoint is a free newsletter that uses both analytic and holistic thinking to examine the wider world. My goal is that you find it ‘worth reading’ rather than it necessarily ‘being right.’ Expect semi-regular updates and essays on a variety of topics. I appreciate any and all sharing or subscriptions, as it helps support both my family and farm.

Earlier this year, I was shopping at my local grocery store when an announcement played loudly through the overhead speakers. It encouraged us to call our representatives and ask them to support Senate Bill 824 and House Bill 1379, which would repeal the ban on alcohol sales in Maryland grocery stores.

Personally, I don’t find much pleasure in either alcohol’s physical or psychological effects and drink it maybe once or twice a year, at most. And I’ve been glad to see the broader societal trends toward sobriety as we’ve tolerated and underestimated the widespread harms of alcohol consumption for far too long.

So the next day, I called all my legislators to tell them I was staunchly against these bills. But not because I’m anti-alcohol, but rather because I’m anti-monopoly

Maryland is one of four states that prohibits the sale of alcohol in grocery stores and other types of general retailers (think Costco, 7/11, CVS, etc.), requiring it to be sold in dedicated alcohol stores.1 While there have been efforts over the years to “modernize” the state’s alcohol sales law and polls show that ~80% of Marylanders support the proposed change, the movement has never been successful. Hope increased this year, as Wes Moore, the current governor, came out in support of the proposed bills.

Despite the general popularity and the support of the governor, the bills were ultimately withdrawn by their sponsors. Maryland’s liquor stores, a subtle, yet great aspect of the state, will survive for at least another year.

Now, this newsletter isn’t necessarily about the alcohol, but I’m going to do a paragraph of anti-alcohol screed because as I said, society continues to underestimate the widespread harms of alcohol consumption

Alcohol kills more people per year than all non-nicotine recreational drugs combined (~175,000 deaths vs. ~100,000 deaths, respectively). Total annual economic losses from excess alcohol consumption were estimated to be ~$224 billion in 2006, (or ~$355 billion in today’s dollars). Alcohol’s link with violent crime is well-documented and according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, ~36% of incarcerated criminals had been drinking at the time of their offense. A meta-analysis published in the American Journal of Public Health suggests that doubling the alcohol tax would reduce alcohol-related mortality by an average of 35%, traffic crash deaths by 11%, sexually transmitted disease by 6%, violence by 2%, and crime by 1.4%.2

With that out of the way, I want to be clear that I’m not a prohibitionist. Alcohol should be legal and ‘widely’ available, within certain restrictions. The reason I support the structure of Maryland’s liquor stores because I’m an anti-monopolist.

“Why are we going to destroy the last vestige of mom-and-pop retail? To achieve what goal? To ensure that billion-dollar grocery chains have the opportunity to avail themselves of even greater profits?” - Maryland State Senator Benjamin Kramer, during a committee hearing on the bills

Over the last several decades, grocery stores have become one of the most concentrated industries. In 1954, the eight largest supermarket chains captured ~25% of grocery sales and this statistic held constant for several decades. Then, the Regan administration directed the Federal Trade Commission to stop enforcing the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936, which prevented grocery suppliers from giving large supermarket chains better prices on the same goods than they offered to smaller grocers. Finally being able to leverage their size over independent stories, a wave of consolidation and expansion began. Today, the eight largest supermarket chains capture ~55% of total grocery sales.

There are even broad swathes of the country where Walmart alone captures >50% of total grocery sales (below). In Barons by Austin Frerick (one of “The Ten Best Books I Read In 2024”), grocery stores (and particularly Walmart) are one of the seven sub-sectors of the food industry3 that he explores and documents how they've twisted the entire food industry for their own profit, at the public's and environment’s expense.

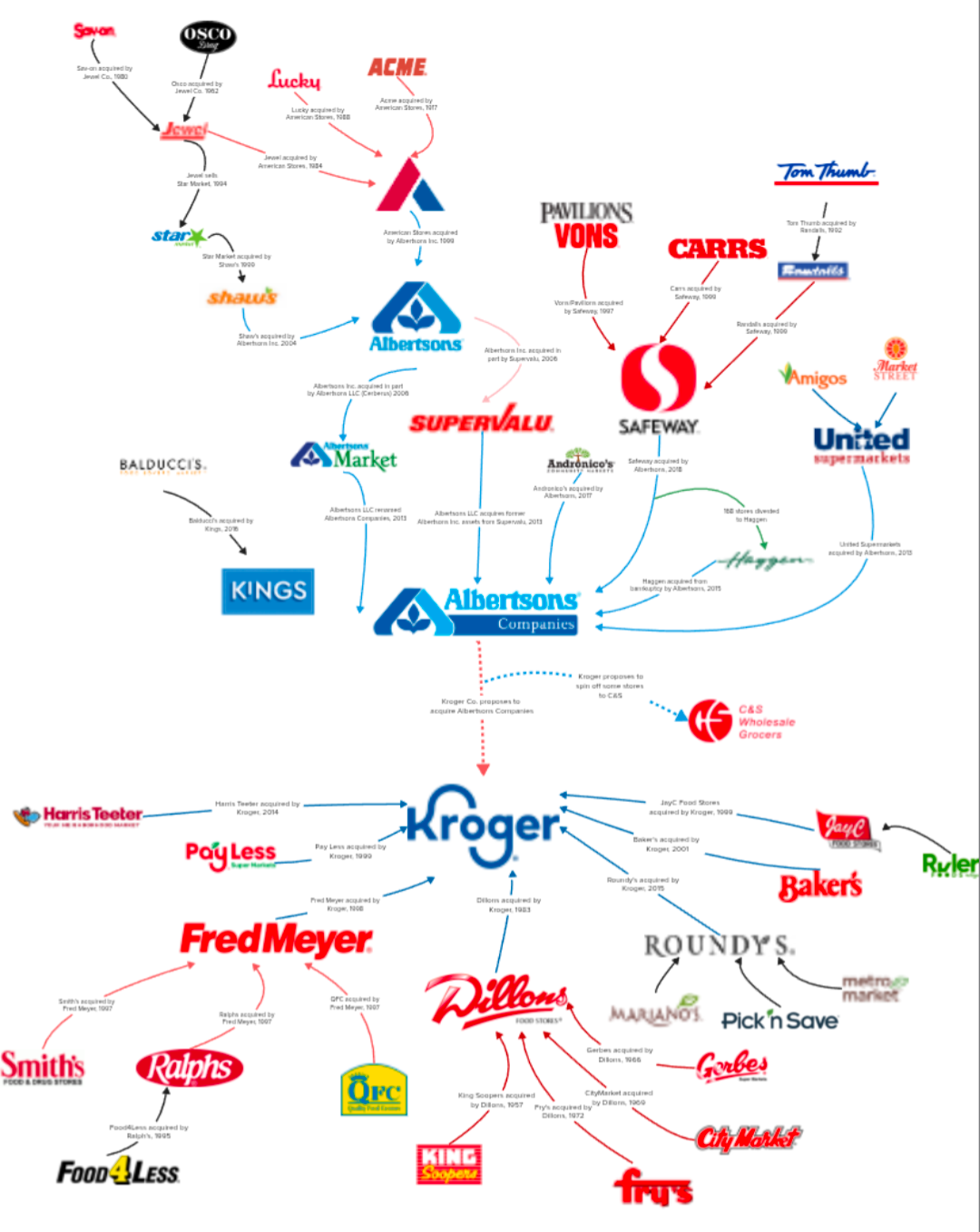

You might not even be aware that this has happened because the corporations hide their acquisitions by retaining the old brand names within a single, labyrinthine corporate structure. When Kroger and Albertsons (two of the five largest grocery chains) proposed to merge in October 2022, the combined company would’ve controlled over three dozen ‘smaller’ and ‘local’ grocery chains.4

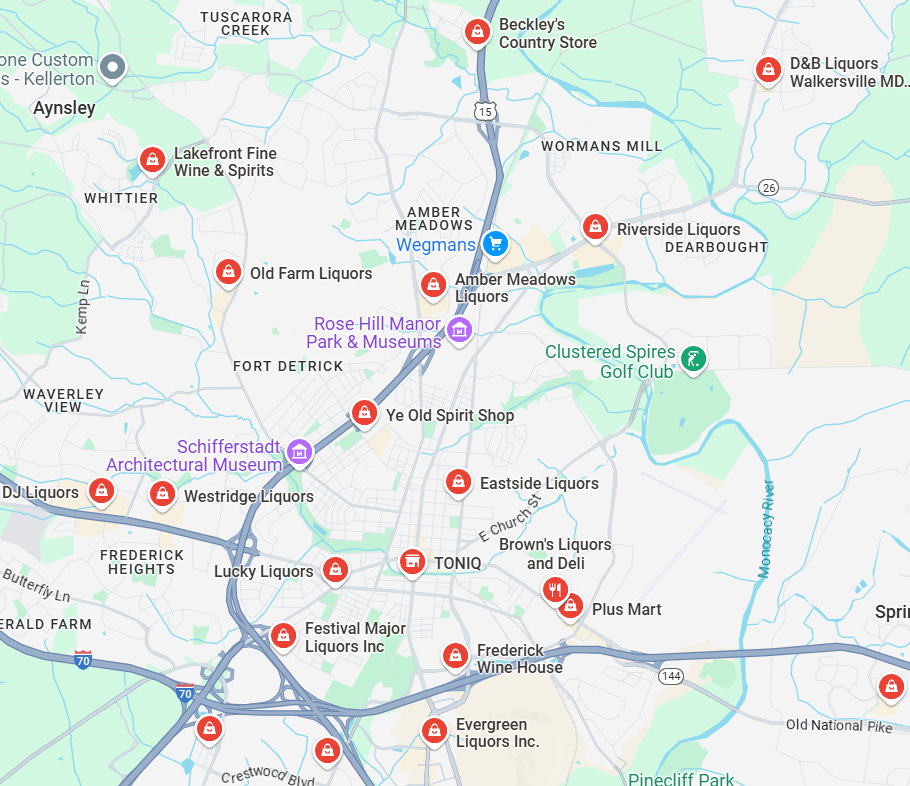

This is where Maryland’s alcohol sales law of 1978 comes in; it is a great example of a subtle yet effective anti-monopoly law. Because grocery stores and other chain retailers are prevented from selling alcohol, a network of local, small businesses survive. Below is the result if you search “liquor stores” in Frederick, MD on Google Maps: mostly local, independently-owned, small businesses.

“If you look at anytime they open up a Costco that sells alcohol, all the other stores in the immediate area close down. No one can compete with Costco’s buying power,” - David, a manager at Lance’s Beer and Wine in downtown Bethesda, MD

My local town has one grocery and three liquor stores. Imagine that the law is changed and the corporate grocery store is now allowed to sell alcohol. Because they operate thousands of stores across the country, they can leverage their buying power from distributors for better prices. This will slowly but surely put the small, independently-owned liquor stores out of business. Perhaps maybe one will be able to survive.

“Yes, but now consumers are benefitting from cheaper prices,” you might reply. And yes, that is true. Alcohol prices would be cheaper. But I want to posit that that is bad, and not only because of the fact that cheap alcohol causes widespread harm across multiple aspects of society.

Besides that, Maryland’s law is a quintessential example of prioritizing resilient local economies over corporate financialization. This has numerous benefits:

Profits stay local: When you shop at a local, small business, the profits from that transaction mostly stay in your community, as the shop owner lives in the area. When you shop at a corporation, the profits get sent back to the corporate headquarters for distribution to shareholders or investment in another geography. When you shop at a local independent business, over three times more money is recirculated locally than when you purchase at a chain stores.

More jobs: Beyond ownership, think of the jobs required to operate the three liquor stores in my town. But if the corporate grocery store could sell alcohol, it would actively destroy jobs. The grocery store would have the same number of shelves, just now some of them would be stocked with alcohol. No new cashiers, no new re-stockers, no new managers, no new accountants, etc. Meanwhile, jobs would be destroyed as the small businesses slowly went out of business.

Small brands benefit: When corporate grocery stores negotiate with distributors, they don’t generally want to buy small batches from local producers; they want to buy in size from other large corporations. This is why independent and dedicated stores (whether it is alcohol or tea or olive oil) generally have much better selections, while corporate chain stores are mainly stocked with brands owned by large corporations like Ab Inbev, Molson-Coors, Diageo, and Constellation Brands, in terms of alcohol. In fact, those ‘craft beers’ at your grocery store are probably owned by ‘Big Alcohol.’ This same phenomenon has played out across nearly all parts of the grocery store: nearly everything in grocery store is owned by a handful of corporate food and beverage companies. Consolidation hurts small players and stifles creative competition.

Local knowledge: Who do you think is more knowledgeable about alcohol brands and taste? The owner or long-time employee at an independent liquor store or the cashier at a corporate grocery chain? Many people bemoan that when they go into a Home Depot or Lowe’s that the workers generally don’t know where thinks are, let alone help them with specific questions, and that they miss the days of the local hardware store. The same logic applies to any specialty retailer. A local tailor will probably be more helpful than Men’s Warehouse. A local tea store will be more knowledgeable than a re-stocker at Safeway.

All of these reasons are why I support Maryland’s current law that prevents grocery and chain stores from selling alcohol. At its core, it is an anti-monopoly law that creates more and smaller companies that a pure market equilibrium would. While that may result in slightly higher prices and slightly more inconvenience for the consumer, which are things that we should with respective to alcohol because of all its negative externalities, but also society benefits by having more resilient local economies: dollars are kept local, there is more competition and innovation between producers and sellers, and stores are owned and operated by knowledgeable craftsmen who can help push consumers toward the right and high-quality products.

We don’t have to cede everything to the short-term logic of cheap prices and corporate consolidation. That’s why, even though I don’t drink, I’ll continue to let my state legislators know that if they want my vote, then they better defend Maryland’s liquor stores.

This law was passed in 1978 and there are ~30 grandfathered grocery/retail stores around the state that retain a liquor license.

Increasing the alcohol tax is one of the most easiest things we could do. Even if all those estimates were only half-as-effective in real life, that would create significant improvement across multiple aspects of society, while simultaneously generating tax revenue and decreasing spending (e.g. less road maintentence and repairs from accidents, etc.), all from a change that doesn’t require any more administrative burden (as it’s just changing the rate of a tax that already exists).

Now go one step further and imagine the benefits if we triple or quadrupled alcohol taxes.

The others are pork, grain, coffee, dairy, berries, and slaughterhouses.

The fact that two of the five largest grocery chains believed that they could successfully merge speaks to the previous lack of antitrust enforcement in the sector. Thankfully, the Federal Trade Commissioner, lead by Lina Khan, a Biden appointee, successfully sued to prevent the merger.

Treating "independent liquor store" or more generally "small business" as the target here seems likely to lead to divergence between the desired and actual outcomes, by propping up zombie businesses. The effect of zombie businesses' money flowing into the local economy isn't even a clear benefit, but a cost, as it propagates corruption through the local economy. And protecting predominantly preexisting businesses doesn't help entrepreneurs creating new types of value, which are the cases that most benefit from local information that hasn't yet been legibilized in ways that Costco can Kroger exploit.

We'd ideally like to let free participants in a market use their local information to decide which sorts of profitable value-added activities should take place locally and which should be purchased from afar. We can do this by articulating what some of the benefits of locally owned and operated independent businesses are, and subsidizing the benefits directly rather than protecting whole categories like "independent businesses that sell people poison to drink," which I think you agree is absurd, even if less absurd than trying to sell them the poison more cost-effectively.

The main benefits I see from local businesses are skin in the game, robustness to supply chain disruptions, and agglomeration.

Skin in the game: Someone who lives within walking distance of their liquor store is more likely to see drunk hooligans trashing the neighborhood as not merely a source of profit, but a problem. Someone who sells a significant share of their wheat to the local bakery they buy bread from is less likely to adulterate their product with stretchers or contaminants, both in order to preserve their reputation and in order not to harm themselves and their friends who eat the bread.

The Econ 101 way to promote skin in the game is to subsidize skin in the game. Businesses in dense, walkable areas that are fully owned and operated by people whose address for tax and school-district purposes is within walking distance could get a tax break or subsidy. Businesses in somewhat larger metro areas owned and operated by people whose address is within daily commute distance could get a somewhat smaller tax break or subsidy. To prevent straw ownership we could insist on unlimited liability, and limits on profit sharing (local owner(s) must have majority interest).

But I think it would make more sense to subsidize skin in the game in kind. Business owners with better incentives don't need to be regulated as strongly. Regulatory barriers are often what block new entrants, while incumbents have already invested the labor of figuring out how to comply or get special exemptions. Large businesses can not only realize regulatory economies of scale, but are also better placed to lobby for regulatory changes that favor them. So the state should offset this by explicitly implementing 2-tier regulation, with much more stringent inspections etc. for businesses with less skin in the game. The same proxies for skin in the game that would apply to a subsidy can be used here.

We might want additional countermeasures to big firms lobbying to scuttle this, like a substantial income tax for professional lobbyists.

Robustness to supply chain disruptions: Local and global supply risks are at least partially uncorrelated. If you're buying some of your intermediate or finished goods from global commodity markets, a local natural disaster doesn't hit you quite as hard. If they're locally produced, it doesn't matter as much if the Houthis attack global shipping or the President imposes big tariffs.

The policy fix here is a little trickier. You need some heuristic for how much localization you want in your supply chain, and the rate of tax or subsidy might need to be dynamically adjusted to match conditions. But the right policy here is something like a reverse VAT tax, in which buyers of a product get a tax break or rebate corresponding to some proportion of the value-added steps in the supply chain that occurred locally. You might want to make the subsidy stronger for contiguous local value-added steps, as these are especially helpful for avoiding external disruption. It's ok if it only works sometimes, and some businesses decide to forgo the subsidy to save on paperwork.

Agglomeration: Firms doing related activities in the same place can exchange information in ways that let them transact more efficiently, and let some businesses develop more suitable intermediate inputs and tools to sell to others with fast feedback loops. For example, a chemist working with a specialized glassblower might be able to get just the right tool for some new procedure much more easily than one buying commodity glassware.

The reverse VAT would help here too. We'd want to make sure it applied to financial services, and especially commercial / business banking.

The city or state could also divert some vocational education funding to subsidized apprenticeships in local businesses, but you'd want to limit the extent of any financial subsidy to a level that's only viable for businesses that are already basically profitable. A streamlined legal / regulatory / administrative framework for creating incentive-aligned apprenticeship arrangements would likely be more important here than a monetary subsidy.

For me this is a convenience thing. I grew up in MD and just thought this was how it was, lived in other states and it was so much nicer to be able to grab a bottle of wine at the grocery store or a 6 pack at a gas station. When I moved back I got reminded of what a pain in the butt it is. I’d also mention for restaurants in Montgomery County, where they’re only allowed to buy from the county, that’s super annoying and arduous. Really good liquor stores that have cool selection and knowledgeable staff will always have a market. I’d love to see Maryland loosen things up and allow bottle shops, like they have in NC where people can consume on site and hang out.