Blue Glade Farm: Master Plan (First Draft)

Seeking input on the plans for our permaculture farm.

The Counterpoint is a free newsletter that uses both analytic and holistic thinking to examine the wider world. My goal is that you find it ‘worth reading’ rather than it necessarily ‘being right.’ Expect regular updates on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic as well as essays on a variety of topics. I appreciate any and all sharing or subscriptions.

In October 2021, my wife and I bought our first home, an 1890s farmhouse with a barn, several outbuildings, and 11 acres in Western Maryland. Since then, we’ve started working to turn it into a permaculture farm. By applying permaculture and agroecological principles to the land, planting a diverse range of native species, both annual and perennial, minimizing to eliminating synthetic inputs and soil disturbance, and incorporating animals, our goal is to integrate our farm into the local ecological whole.

While our first year included many projects (our first annual report can be found here), much of it was spent simply observing the land and learning the rhythms and patterns of the local ecology. We also continued to learn through books, Youtube, and Twitter.

Now that we’re ~1.5 years into this, I felt it time to put together a ‘master plan’ of what we’d like to do with our little patch of Earth. As a career scientist and trained philosopher, I’m quite comfortable publishing my work for critique and of accepting my own ignorance. This is very much a first draft that needs feedback, critique, and commentary. We’d appreciate suggestions from anyone.

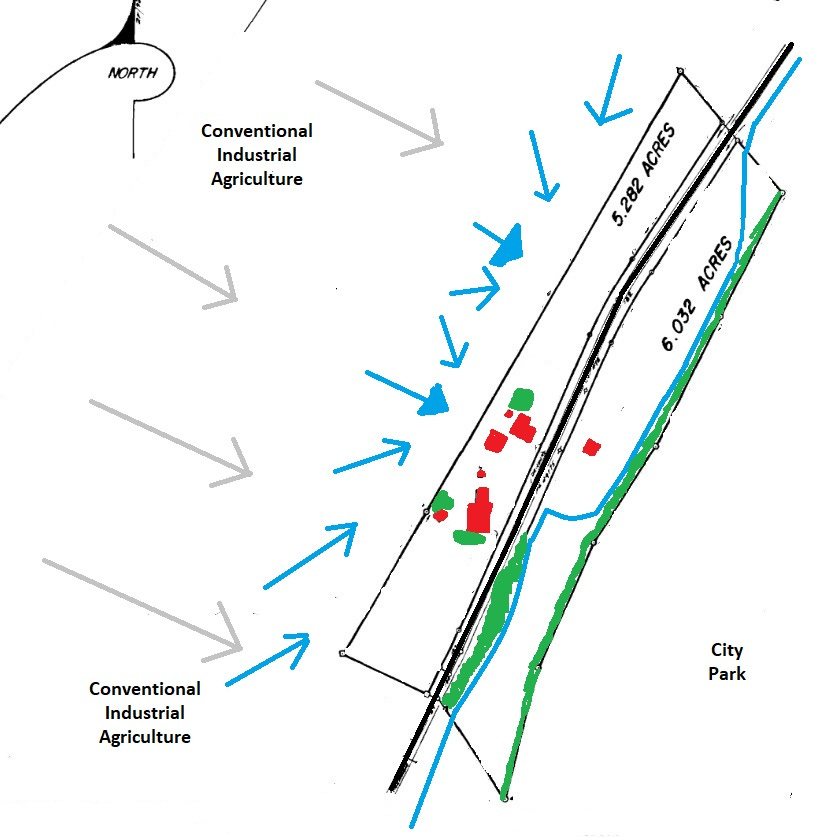

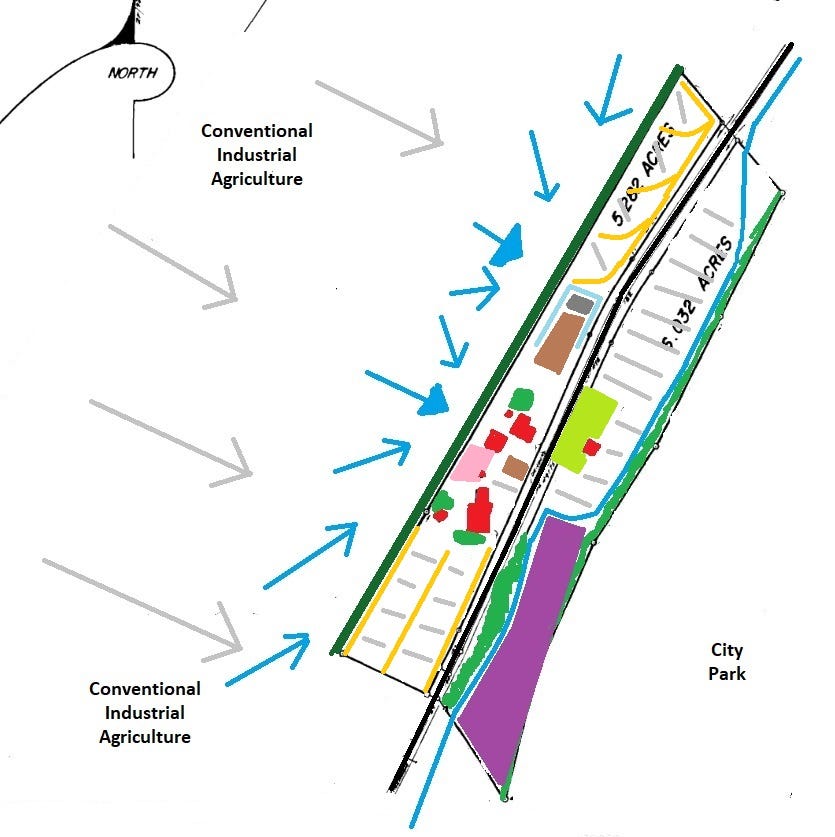

Below is an edited version of the plat that came with the house. Our house, barn, and outbuildings are colored red and mature trees are green. Our acreage is split by our road and there is a creek in our eastern field.

Our western side is surrounded by several hundred acres of conventional industrial agriculture: wide open fields on standard corn-barley-soybean rotation. With no breaks, we are exposed to strong winds throughout much of the year (gray arrows). Additionally, all water drains toward the creek through out farm. I’ve marked the general direction of flow (blue arrows, with solid arrowheads marking the low points). Given that almost the entirety of our land is pasture, our land contributes to both problems.

These issues serve as the foundation for our highest level vision for the farm: as a living riparian buffer around the creek that acts as both wind break and water filter, while simultaneously being a ‘food forest’ that produces food and fiber for our family and community, and habitat for the hundreds of species involved in the local ecology.

So, how do we achieve that?

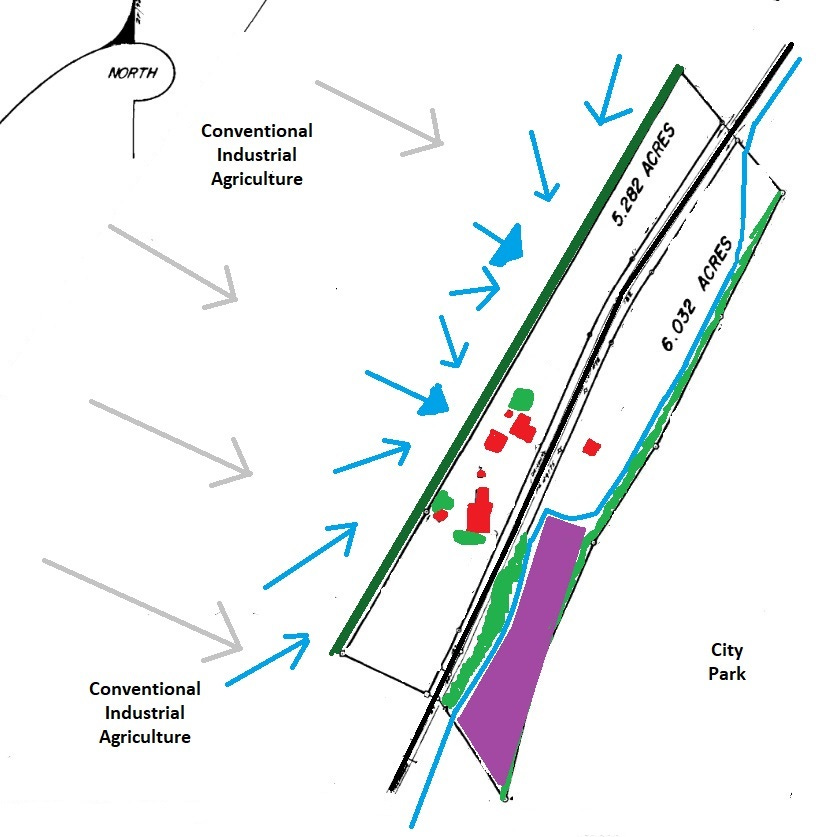

First, we have already begun planting a thick hedgerow along the entire western edge of the property (dark green line). By planting species like hazelnut, black locust, conifers, holly, serviceberry, basswood, cypress, and others, not only will this hedgerow create a significant windbreak, but it will provide important habitat for numerous species while also producing food and fiber for the farm. Here is a recent piece in Civil Eats on the importance of hedgerows.

Second, we will place the bottom portion of the creek field (purple) into the Conservation Reserve Easement Program (CREP) through the FSA. I always wanted to place ~10% of my land in conservation (think of it as an ecological ‘tithe’) and that portion of the field is just about that. In exchange for agreeing to no agriculture with that acreage, the FSA will plant it with native trees and give us a small rental payment for 10-15 years. These trees will provide important habitat, sequester carbon, and help stabilize the creek bank.

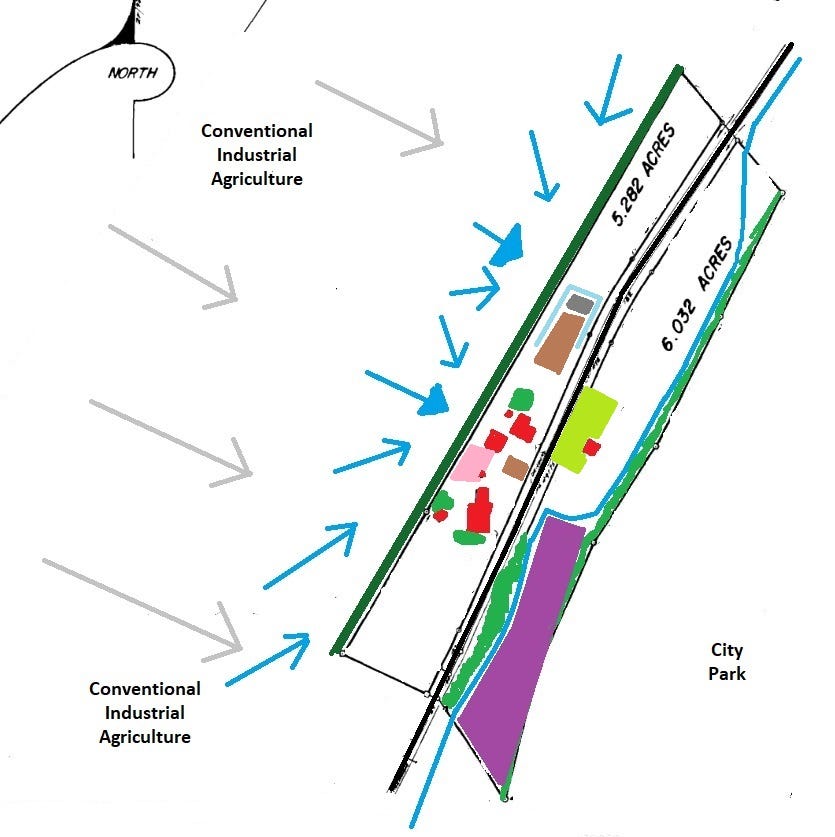

Next, we need to get the fertility and nutrient cycling going. One easy way to do this is with compost, which we've already invested heavily in (see our first annual report). The next step will be a flock of chickens, as they not only upcycle kitchen scraps, inedible produce from the garden, and insect and worm protein, but they do it while producing protein-rich eggs for us and rich fertilizer for the garden. We have turned the old spring house into a coop and plan to fence in a large chicken yard around it (pink area). By planting with chicken-edible plants (comfrey, blackberries, etc.) we hope to reduce feeding costs. And by regularly filling the yard with fresh wood chips and sawdust (carbon), which the chickens will scratch and defecate on (nitrogen), we will produce a rich compost for our gardens. Edible Acres on Youtube has a fantastic series on chicken compost yards (and their other videos are excellent as well).

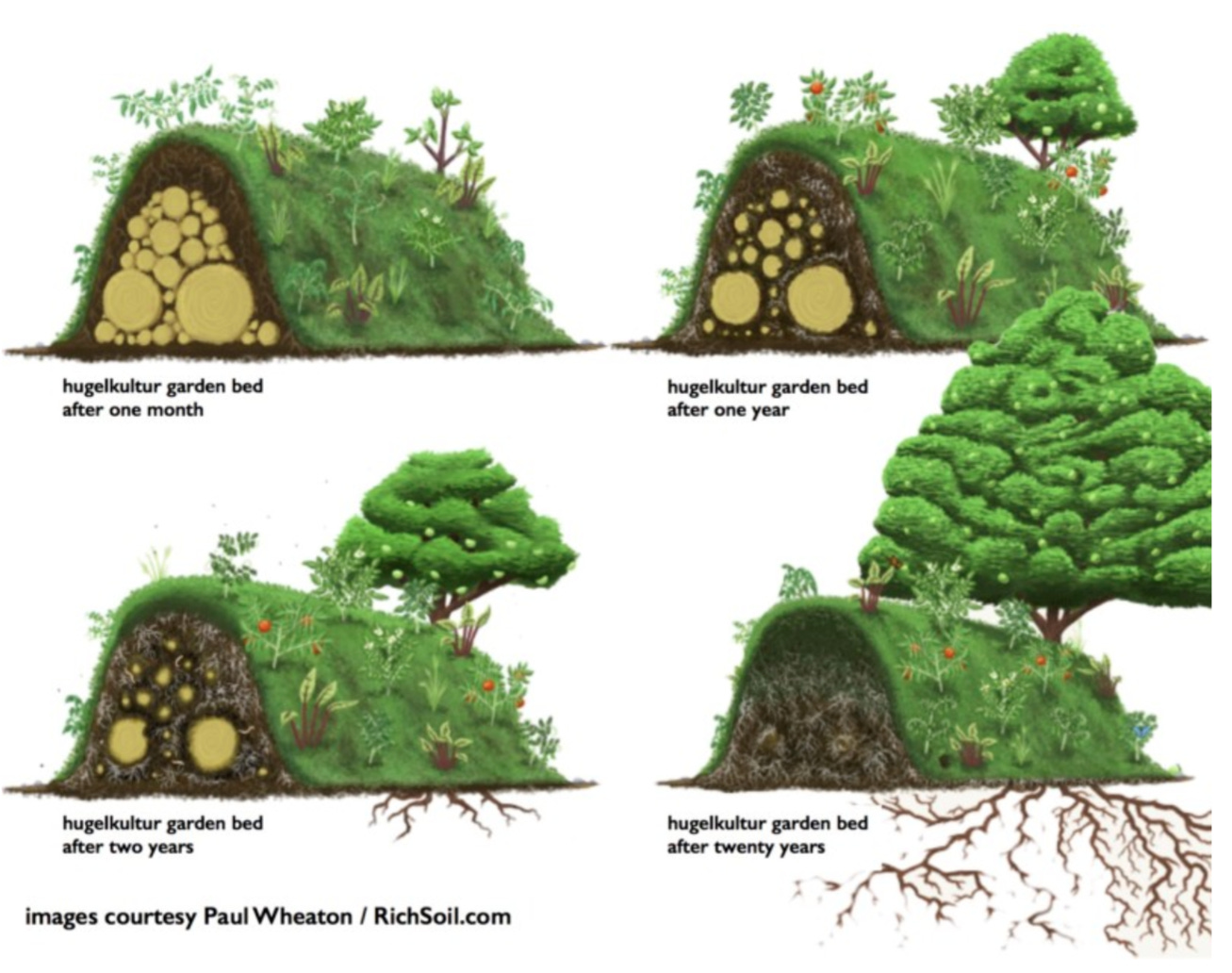

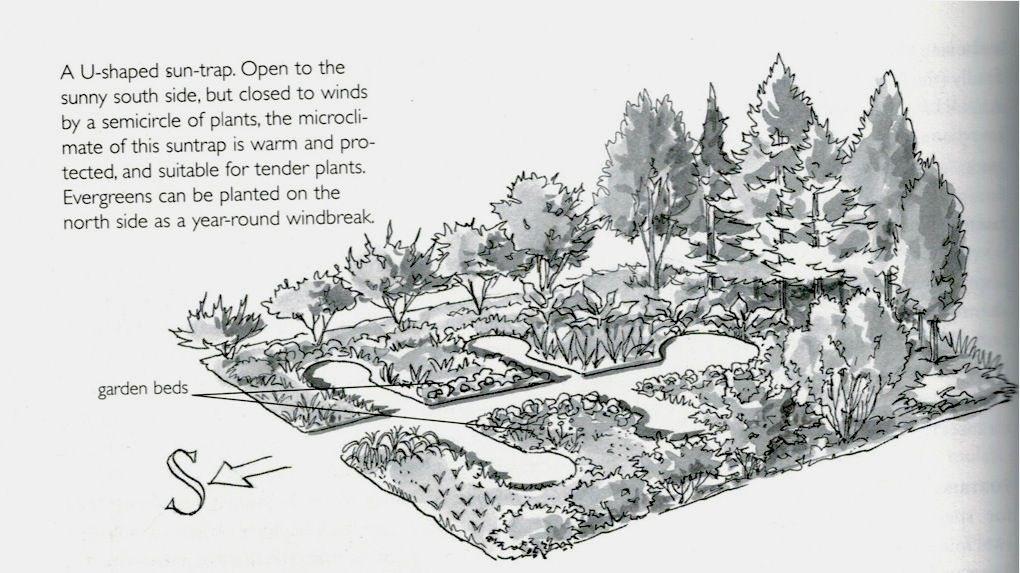

Speaking of gardens, we have started an annual garden (small brown square) and plan to expand it (large brown square). For the large garden bed, we plan to combine the ideas of a sun-trap garden with hügelkultur walls (light blue lines surrounding the brown square). The goal with this combination is to produce an artificial valley, meaning a warmer microclimate, less wind exposure, and better water retention for the garden. Moreover, we are applying for an Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) through the USDA to build a high-tunnel (gray square north of the garden bed) which would allow us to extend the growing season even further.

Next, we are planning a paw paw orchard (lime green box) in the creek field. The eastern United States is the only place in the world where paw paws are native. Most importantly, they produce a delicious fruit. While economics is not our primary concern, paw paws do sell for a high dollar amount, ~$12/lb in my county. By establishing a high-density orchard, paw paw will serve as one of our cash crops.

The last major part of the plan is silvopasture: integrating trees and livestock. Lines of trees (golden lines, not exact) along with portable electric fence (gray lines) will form small paddocks.1 The goal is to be able to create 60-90 small paddocks and rotate 3-4 beef steers2 to a new paddock each day. This simulates their natural grazing patterns in the wild, allows the pasture time to rest and re-grow between grazings (which will also be important habitat for many species since it won't be mowed/grazed for those 2-3 months) and the animal’s urine and feces provides nutrients for trees, such as chestnuts and pecans, which are strong annual producers of nuts (and perhaps some oaks to distract the squirrels) and provide habitat for dozens of species (essentially the oaks). The trees will be placed on contour with small swales when possible, to help with water infiltration and prevent runoff and erosion.

We are starting with beef steers because it is what I am most familiar with (I grew up on a small cattle farm), but meat chickens, sheep, and/or ducks are also a possibility in the future.

Both nuts and animal protein serve as important winter foods as they store much more easily than fruits and vegetables. The tree trimmings can also be cycled back into our composting systems by turning them into wood chips. Later on, chestnut and oak are valuable lumbers while hickory is one of the best firewoods.

There are several other aspects to the farm that didn’t find a place on the map, such as the several hot compost systems we’ve already built and that we will continue to expand, the riparian buffer along the creek with willows, cattails, swamp white oak, and other species, the bee hives that we’ve arranged with a local apiarist to place on the farm, the many wildflowers we’ve planted and will continue to expand, and finally some construction projects like rainwater capture systems (definite), solar panels (possible), bird habitat such as normal bird houses and a owl roost (definite), and a compost toilet (possible).

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for tolerating my terrible Microsoft paint edits. I hope everything made sense and that you are able to envision the farm as we do: a large-scale, food-producing, ecological-habitat riparian buffer.

To be clear, we are only in the very first (or zeroth) stage of much of this and we truly are looking for feedback; we want our farm to be as ecologically successful as possible. If you have any ideas, comments, concerns, or questions, please let us know!

With the creek field being narrow and flat, the portable electric fence will simply be strung between the fence lines, no trees.

Maryland does not require a nutrient management plan under 8000 lbs live weight. We will see how things work with four steers before we expand past that.

Hi Patrick. I just subscribed to your Substack newsletter. Super fun reading your plans. My only suggestion is that you put a key in your drawings for reference.