Pandemic Lesson #1: Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Dust

The first of five lingering thoughts that I'm taking away from the pandemic: we've underinvested in the physical world.

The Counterpoint is a free newsletter that uses both analytic and holistic thinking to examine the wider world. My goal is that you find it ‘worth reading’ rather than it necessarily ‘being right.’ Expect regular updates on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic as well as essays on a variety of topics. I appreciate any and all sharing or subscriptions.

In early 2020, everyone went inside their homes and logged onto the internet. Subscribers for streaming platforms hit record numbers. Groceries were ordered through Instacart. Masks were bought on Etsy. Social media usage soared. As we all awaited the next presidential statement, Twitter saw it’s largest growth in over five years. Peloton users have more than tripled. With the rise of Roblox and other platforms, the Metaverse became the hottest investing trend; Facebook even changed their name to Meta. E-commerce sales experienced years of growth in just a single quarter and, despite headwinds from both supply chains and inflation, they haven’t slowed.

The technological story of the pandemic is very easy to tell. And it’s correct; we all really did use Netflix, the President really did tweet, and your grandparents really can use Zoom now.

But that being said, the untold narrative of the pandemic is of the importance of and the chronic underinvestment in the physical world.

The most obvious example is SARS-CoV-2 itself. The risk of a ~0.1um coronavirus from bats1 was wholly predictable2, yet pandemic prevention offices were closed, personal protective equipment wasn’t stockpiled, and hospitals were operated for efficiency rather than resilience-to-known-risks. The virus spread through both airborne droplets and aerosols, which could’ve been controlled through physical barriers (i.e. high-quality masks such as KN94/95s and N95s) and improved ventilation (both sanitization and circulation of air), if we had simply invested in them. While venture capital funding continues to hit new all-time highs, public health funding declined over the past decade. In real terms, the CDC’s budget was flat over the entirety of the 2010s.

But the de-prioritization of the physical world has been much deeper than just public health and the pandemic.

Think about the last two years:

Winter storms caused the massive Texas power crisis that killed hundreds of people. Texas had previously been warned that it’s energy infrastructure was inadequate.

Nearly five million acres burned in Californian wildfires in 2020, killing sixteen people, displacing thousands, and exposing tens of millions to toxic air. Climatologists have long warned that climate change will increase the frequency of wildfires.

Automobile and other electronics prices have surged, in part due to semiconductor shortages. The United States has been losing market share of semiconductor manufacturing for decades.

But it’s not just natural disasters such as pandemics, ice storms, and wildfires that we didn’t prepare for. It’s not just niche products like semiconductors that we didn’t build.

Hundreds of rural hospitals have closed since 2010. The pandemic accelerated this trend. Over the next decade, the American Academy of Medical Colleges estimates the United State’s physician shortage will increase to at least 38,000.

The Forbes Avenue Bridge collapsed in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in early 2022, only the last illustration of the United State’s crumbling infrastructure. The Army Core of Engineers gave the nation’s infrastructure a “C-” overall grade in 2021. Many individual states rate lower.

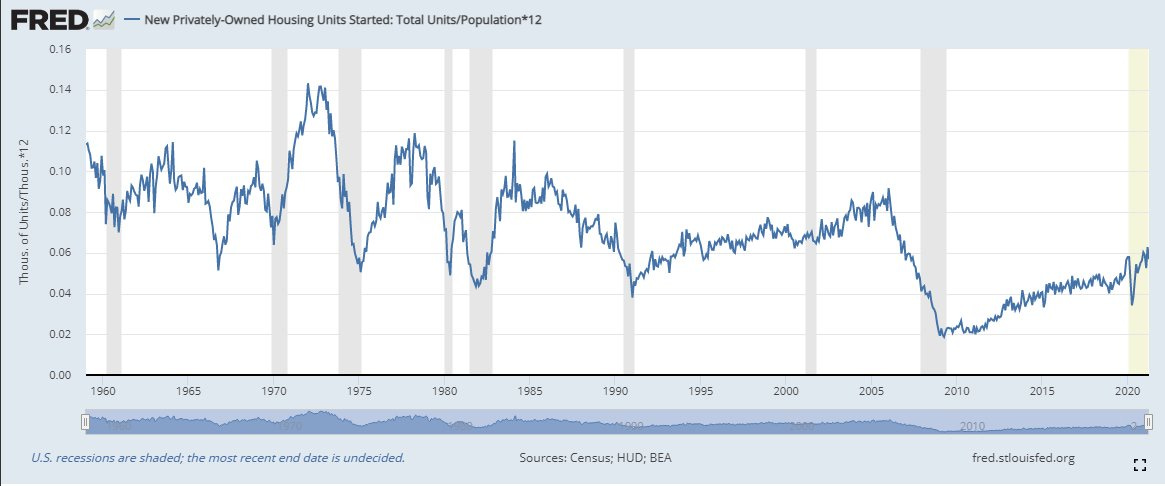

House prices have surged nationally in part because the inventory of US homes is currently at all-time lows. Since the Financial Crisis we have basically stopped building homes, with population-adjusted housing starts lower every year between 2008 and 2018 than any year since 1960. Even the current “construction boom” seems recessionary when compared to historical data.

So it’s not just natural disasters we aren’t investing in; it’s not just niche products whose manufacturing we’ve exported. The United States has stopped building houses, hospitals, and critical infrastructure.

The totality of our underinvestment in the physical world is perhaps illustrated best by the current crisis of the Ukrainian-Russian war. Not only do wars consume many fossil fuels themselves but Russia is a major fossil fuel exporter, and their involvement in the conflict potentially threatens that supply. This has caused the price of oil to surge to nearly 20-year highs.

One side of the political spectrum will say that this is because we’ve underinvested in the supply of American-produced fossil fuels. The other side of the political spectrum will say that this is because we’ve underinvested in carbon-free energy that would’ve decreased demand for fossil fuels. Regardless of where one falls in this debate, the problem is a lack of investment in the real world, the world of atoms, earth, air, water, and people.

In the award-winning film, Gladiator, the former-Roman-general-turned-gladiator Maximus Decimus Meridius pauses before every fight, bends down, and grabs some dirt that he rubs between his hands and then smells.

Early in the film, Maximus quips that “dirt washes off easier than blood,” but I’ve never understood that to be the real reason he does this. Maximus’ home is a farm in Spain and there is no place he’d rather be than on this farm with his family. I’ve always believed that he smells3 the dirt in order to ground himself, remind himself of what is truly important in this life.

This newsletter has not been an under-handed dig at technology. In fact, I believe that technology is all-in-all beneficial for society. Perhaps the best example of this is the advent of the mRNA technology that Pfizer and Moderna used to create our life-saving vaccines.

But perhaps we’ve drifted too far into the technological and forgotten where we’ve come from and the importance of the physical world. If so, this is okay. All we have to do is stop, bend down, and smell the dirt between our feet.

There is universal agreement that SARS-CoV-2’s ancestor was in the native bat population. Whether or not one believes the intermediary step was an exotic animal wet market, the Wuhan Institute of Virology, or some other route, is a separate (and unresolved) issue.

I’ve shared the last sentence from this 2007 paper numerous times: “The presence of a large reservoir of SARS-CoV-like viruses in horseshoe bats, together with the culture of eating exotic mammals in southern China, is a time bomb. The possibility of the re-emergence of SARS and other novel viruses from animals or laboratories and therefore the need for preparedness should not be ignored.”

Our sense of smell is intricately linked with memory and emotion.