Thoughts on "Outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 Reinfection"

Analysis of a recent study on CoV-2 reinfections

The Counterpoint is a free newsletter that uses both analytic and holistic thinking to examine the wider world. My goal is that you find it ‘worth reading’ rather than it necessarily ‘being right.’ Expect regular updates on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic as well as essays on a variety of topics. I appreciate any and all sharing or subscriptions.

On June 17th, a pre-print of “Outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 Reinfection” by Drs. Ziyad Al-Aly, Benjamin Bowe, and Yan Xie was published online.

Its abstract concludes: “The constellation of findings show that reinfection adds non-trivial risks of all-cause mortality, hospitalization, and adverse health outcomes in the acute and post-acute phase of the reinfection.”

This study and its claims garnered attention online, including a Twitter thread by Dr. Eric Topol that started “COVID reinfections are not benign,” and ultimately culminated in Dr. Topol writing “A Reinfection Red Flag” on his Substack.

Unfortunately, it’s a bad study.

And I don’t mean bad as in low-quality. In fact, its a good study and I have great appreciation for Dr. Al-Aly’s team’s series of papers on COVID-191.

By “bad,” I mean that its methodological structure severely limits any conclusions that can be drawn from it. Moreover, because of its study population, any conclusions we do draw from it cannot be generalized to the broader population.

And unfortunately, none of the above paragraph is mentioned by the vast, vast majority of people or news organizations when they discuss it on social media or the news.

The Study’s Structure

The study compared outcomes in three cohorts: CoV-2 first infection, CoV-2 reinfected, and non-infected.

The CoV-2 first infection cohort contained individuals that tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 between March 2020 and September 2021. The date of an individual’s first positive test is labeled “T0” for the purposes of the study.

The CoV-2 reinfected cohort contained individuals who experienced a reinfection, defined as a positive SARS-CoV-2 test more than 30 days after the first infection. The date of an individual’s reinfection is labeled “T1” for the purposes of the study.

Finally, they constructed a non-infected control group by identifying individuals with no record of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test between March 2020 and September 2021.

Below is Supplementary Figure 3, which outlines the construction of these cohorts:

While the authors had very good reasons for this construction, it also has limitations.

Limitation #1: the requirement that individuals had tested positive to be included in the CoV-2 infected groups. We've known that throughout the pandemic, both asymptomatic illness and access to testing have been issues when trying to identify cases. Since a positive test was required, this means that there is likely a cohort of patients that was CoV-2 infected but excluded from the CoV-2 infected groups. The authors’ other research is clear that negative outcomes scale with disease severity (i.e. asymptomatic infections would have the least outcomes). This means that they are concentrating the CoV-2 infected groups toward outcomes by excluding individuals that were asymptomatically-infected.

Limitation #2: the exclusion of anyone that died within 30 days of enrollment. From the methods section, under the “cohorts” paragraph: “We excluded those who died during the first 30 days after the first positive SARS-CoV-2 test.” This removes anyone that died from CoV-2 during the acute phase of their first infection, which obviously removes a meaningful amount of outcomes from the CoV-2 infected group.

Again, I want to emphasize that the authors had very good reasons for this construction. Since they are studying outcomes from CoV-2 infection and reinfection, it is standard to require a positive test. This is a limitation of all CoV-2 research that requires a positive test in a population where testing was neither mandatory or random. Since reinfection necessarily requires an individual to survive their first infection, it would also skew things to compare a cohort with a percentage of dead individuals (the CoV-2 infected but including deaths) to a cohort with no dead individuals (the CoV-2 re-infected).

The Study’s Comparison

With the three cohorts constructed, the authors balanced them and then examined and compared the outcomes in the three populations. Outcomes included “all-cause mortality, hospitalization, having at least one sequela, as well as organ system disorders including cardiovascular disorders, coagulation and hematologic disorders, diabetes, fatigue, gastrointestinal disorders, kidney disorders, mental health disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, neurologic disorders, and pulmonary disorders.”

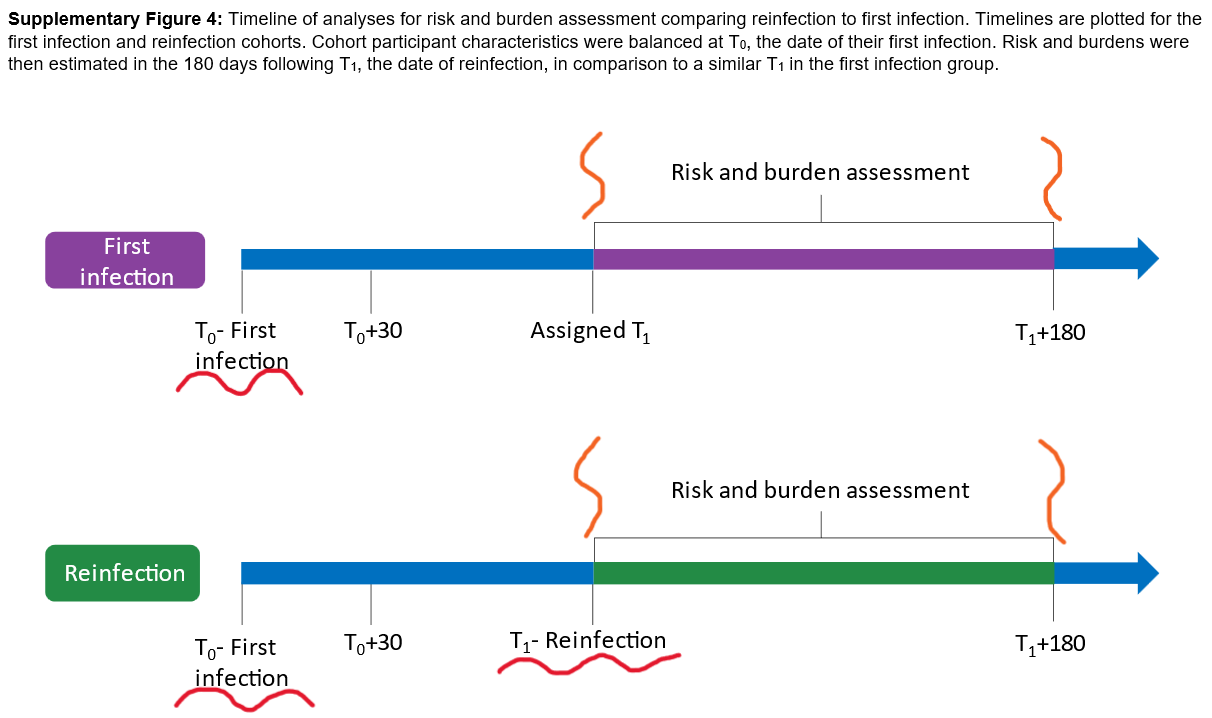

But when exactly one balances and compares is important. They provide that information in Supplementary Figure 4, which is below. For clarity, I’ve underlined the infections with red squiggles and bracketed the comparison period with vertical orange squiggles.

Limitation #3: The CoV-2 infected group had more recovery time than the CoV-2 reinfected group. The groups were balanced at the first infection (T0). Again, there are good reasons to do this. It controls for the variant of first infection (i.e. you wouldn’t want to compare WT-first infections to Alpha-first infections to Delta-first infections). It also controls for standard-of-care during first infection (i.e. you wouldn’t want to compare first infections before dexamethasone was an approved treatment to first infections when dexamethasone was a standard treatment).

But it isn’t until after the reinfection that both risk and burden assessments are performed. This means they aren’t accurately comparing the two groups!! The CoV-2 infected group had more recovery time (the time between infection and assessment) before their risk and burden assessment.

Limitation #4: The assessment period includes the acute phase of the reinfection period. The risk and burden assessment can occur anytime between the refection (T1) and for six months afterward (T1 + 180). But if the assessment occurs within 30 days of the reinfection (the acute phase of disease), then obviously the reinfected group will have more outcomes; they are actively infected!

The authors even make both these clear in Figure 3 (below), where they show the burden of the reinfection group in 30-day increments after reinfection. For every outcome, the burden decreases over six months and is continuing to decrease at six months! Recovery is important with COVID-19 (and any disease) and the first infection group was allowed more time to recover. Additionally, they’ve even labeled the acute phase here! Yet that’s included in the grouped data.

The Study’s Cohort

Who exactly is studied can greatly alter outcomes. For example, we know that age, co-morbidity status, and vaccination status are the three biggest predictors of severe outcomes from COVID-19.

The demographics of the study’s cohorts are listed in Supplementary Table 1. A version is below (I removed some lines for purposes of the screenshot; don’t worry, the removed lines will come back. I also added the colors).

Limitation #4: This is a study of unvaccinated elderly people. Average ages for each group are highlighted in green and unvaccinated rates highlighted in yellow. This is worthwhile data to collect. It would be extremely relevant if we didn’t have a vaccine. But now we do and most seniors are vaccinated.

And if you’re now a vaccinated 30-year-old, then none of these numbers apply to you in the slightest. Are they directionally correct? Of course. Obviously one should avoid any infection. All infections (whether primary or a re-infection) of any virus (whether CoV-2, influenza, or another) add some non-zero amount of risk. But we didn’t need this study to know that.

But the media and the ‘talking heads’ never state this. They simply say “COVID-19 reinfections increase one’s risk of hospitalization by 3x,” while leaving out these massive limitations and caveats.

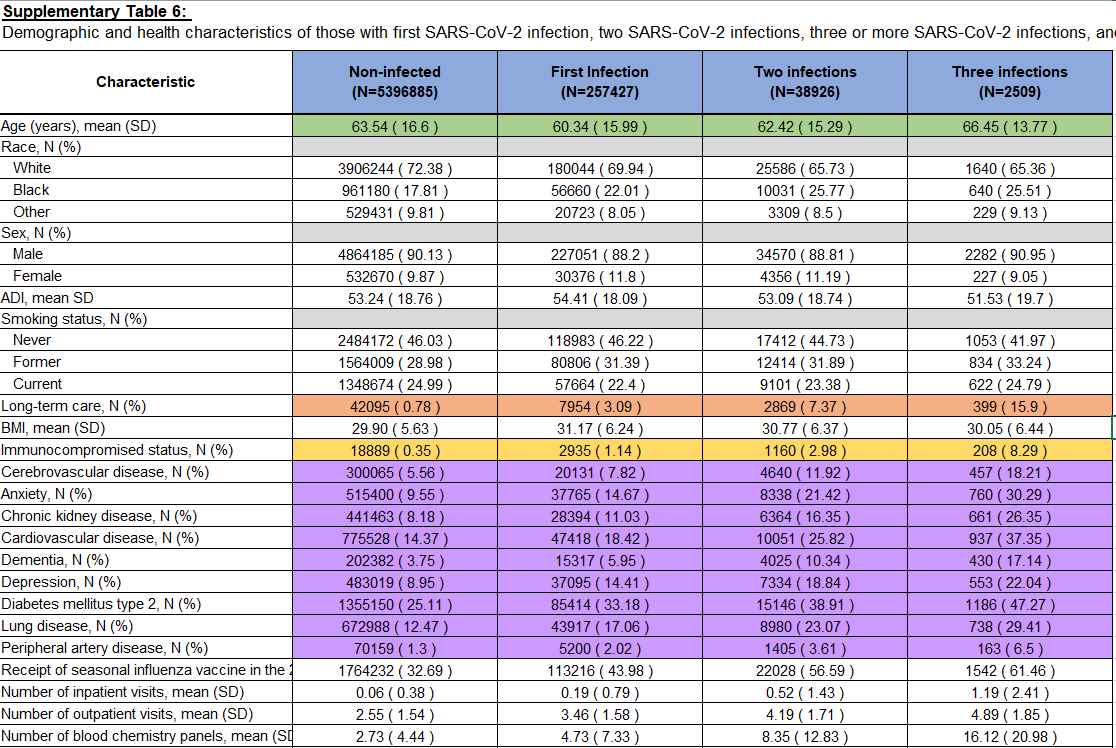

Finally, at one point, the study analyzes multiple re-infections. They list the demographics breakdown in Supplementary Table 6, which is below (again colors added while most of the removed lines from the first demographic table have been brought back).

Limitation #5: Reinfections are rare and occur in older, unhealthier, and frailer people. It’s a cohort effect!!

Notice that with every infection there is an exponential decrease in the number affected from N = 257,427 for first infection to N = 38,926 for two infections and N = 2,509 for three infections (blue line). Reinfections were not common during the study timeframe.2

More importantly, look at the characteristics of who is getting reinfected. They are older (green line), more likely to be in long-term care (orange line), more likely to be immunocompromised (yellow line), and more like to have cerebrovascular disease, anxiety, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, dementia, depression, type 2 diabetes, lung disease and peripheral artery disease (purple lines)!! And these differences are extremely large!!

Like so large, they also certainly can’t be fully controlled for.3

To try to illustrate and example, biological men have a small amount of breast tissue and rarely, they get breast cancer. And when men get breast cancer, on average, they have worse outcomes than women (likely because of a lack of awareness and screening). But no one seriously claims “well if we control for incidence, biological men are more affected by breast cancer than women,” because the incidence is rather important. Breast cancer is rare in men while it's common in women.

Here is a similar phenomenon. If you’re vaccinated, younger, and healthier, then reinfection is rare. It’s merely a sub-group of extremely sick and frail people that keep getting reinfected. And there is no amount of statistics that can change the incidence itself.

To summarize, science is hard. Here is a study, that while being well-designed, is also severely limited. And while I do wish the authors were more explicit about these limitations, I’m mostly irritated at how social media and news organizations disseminate science, amplifying weak or preliminary studies, bypassing any discussion of limitations, or just extrapolating incredibly bad evidence.

To reiterate, this study on reinfections has severe limitations. I have extremely low confidence on any of its exact numbers or conclusions other than the very, very high level “reinfections carry a non-zero amount of risk,” or “unvaccinated and frail elderly have bad outcomes with COVID-19.”

I would note again that this study occurred from March 2020 to September 2021, i.e. before Omicron. Reinfections are more common now. But that is to be expected as the virus evolves. Think of influenza. Each individual will probably be infected with influenza several times during lifetime because of its antigenic drift.