Steelmanning Degrowth: The Catalytic Society

Degrowth is consistently maligned and misrepresented by both "growthers" who strawman it and radical "degrowthers" who are actually primitivists. I am here to defend it.

The Counterpoint is a free newsletter that uses both analytic and holistic thinking to examine the wider world. My goal is that you find it ‘worth reading’ rather than it necessarily ‘being right.’ Expect monthly updates and essays on a variety of topics. I appreciate any and all sharing or subscriptions.

Author’s note: this post is long, so if you’re reading in email, you’ll need to click the title of the post or the “view entire message” that will appear at the bottom.

Degrowth is an increasing popular response to our current ecological crisis. At the highest level, it advocates for reducing society’s material and energy consumption.

Degrowth is also one of the most consistently maligned and misrepresented perspectives, subject to constant strawman arguments. To be fair, some of this is the result of insane prescriptions by its most revolutionary advocates. But rarely is an earnest attempt made to reckon with a serious descriptive version of a ‘moderately-radical’ degrowth.

I wouldn’t call myself a “degrowther,” per se. My day job is engineering next-generation cell and gene therapies, where a certain amount of techno-optimism is basically a requirement. In fact, I’ve written about the optimism that I have about humanity’s future and our ability to use both technological and cultural change to advance through the problems that we face.

But the smartest and wisest people are able to find value in a wide variety of perspectives and philosophies, and then synthesize that learning into their own views. In that vein, I have taken Degrowth seriously, and not just written it off by its caricatures. And not only do I think there is wisdom within Degrowth, I also think it’s perfectly compatible with techno-optimism, so I am here to ruffle some feathers and defend it.

Metabolism

The human body is the foundation of our civilization. Our opposable thumbs provide the fine motor control required for tool manipulation and writing. Our cardiovascular-pulmonary system allows for endurance, a rare trait which gave us an unusual advantage in hunting, even without tools. Most obviously, our central nervous system grants us the intelligence and abstract thinking that we utilize for, well, everything.

Another one of these examples is our metabolism. Its most obvious advantage is our wide omnivore diet, which allows for unparalleled adaptability in our food selection (especially when combined with our ability to prepare and cook). But our metabolic advantages don’t end with just what we eat; the human metabolism has several adaptations that increase our flexibility in storing and using the energy that we consume.

This flexible metabolism leads to a profound range in body types. Think of the differences between the bodies of world-class marathon runners and sprinters, or between body builders and sumo wrestlers. All achieve peak performance within their domain while having a vastly different bodies and metabolisms than each other. Even within a single individual, the right regimen and substances can quickly induce profound shifts in body type and metabolism.

There is no debate that professional body builders and sumo wrestlers aren’t successful at what they do. In fact, they’re rather impressive. But there is also general acknowledgment that their metabolisms come with long-term tradeoffs. It is well-documented that both steroids and obesity cause severe, long-lasting, and in some cases, irreversible damage.

Yet when someone says “don’t use steroids” or “maintain a proper weight,” we understand that they aren’t suggesting to become emaciated like Christian Bale in The Machinist. That also has clear long-term negatives. There is an implicit moderation in statements like these that we all understand: remain physically active, eat a balanced diet of diverse whole foods, improve sleep quality, drink plenty of water, stretch regularly, maintain robust social connections.

But if we recognize that the Earth and the biosphere are also biological systems, that means they also have a metabolism, and that the huge bolus of non-renewable fossil fuels that have enabled techno-industrial society and mass consumption are having impacts on that metabolism much like steroids or obesity: short-term success but also long-term damage.

When Degrowth suggests we reduce our resource and energy consumption, that should be interpreted as a statement of moderation, not as the utter dismantlement of techno-industrial society and a return to hunter-gather societies (that is Anarcho-primitivism, not Degrowth). It is the use all of our technological knowledge and cultural change to right-size modern society’s metabolism for long-term health and stability while still providing a sufficient quality-of-life for all.

The Bad Chart

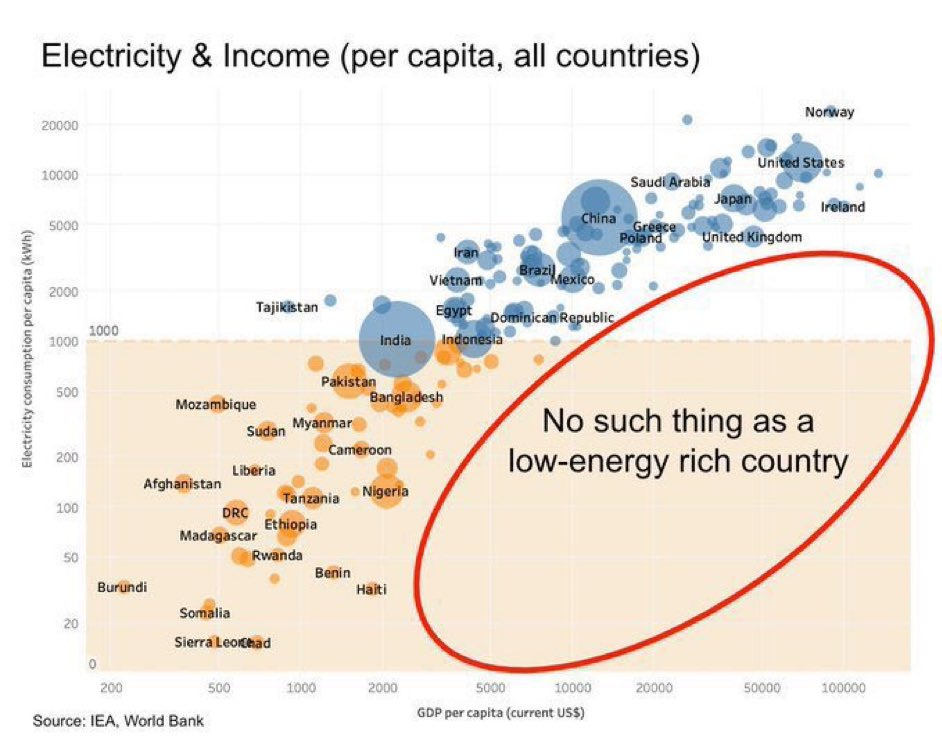

First, let’s deal with one of the most annoying charts on the internet. It is common for “Growthers” to dunk on Degrowth by posting the below chart along with some quip.

The most obvious problem with this chart is that it has the opposite causation of what posters like to imply. It’s not that the rich countries are rich because they consume electricity, they consume electricity because they are rich. It’s merely showing that rich nations consume more. This is a well-documented phenomenon that holds true even within countries (e.g. the top income decile in the US has per capita carbon emissions ~26x that of the bottom decile).

Stemming from that, we should recognize that consumption itself isn’t an end goal. What we should want is “a long, healthy life,” not “electricity consumption.” Sumo wrestlers and steroid-using body builders consume more energy than the average person, but they die younger and with more health issues, exactly the opposite of a “long, healthy life.” Never has someone on their death bed wished, “If only I had consumed more energy.”

But the worst part of the graph is it purposefully uses a log-log scale to distort and eliminate visible differences that prove its own absurdity. A linear-linear version of the global chart can be found here (you may have to adjust the axis settings), but even that version has a lot of outliers that distort (tax havens, such as Luxembourg and Ireland, distort the GDP per capita axis, and very hot climates such as Singapore and Qatar, distort the energy use per capita axis).

Below is a graph of energy use per person over time for five developed nations.

The United States consistently consumes ~2x the energy per person of Japan, France, Denmark, and the United Kingdom. If financial or energetic consumption unequivocally caused positive outcomes, we’d expect the United States to perform better on all quality of life metrics. Yet it doesn’t. For many it performs worse.

Not only does the United States perform worse in many of these desirable metrics, it also performs worse in many undesirable statistics: it has a higher murder rate than any developed nation, more alcohol and drug use disorder deaths, and is essentially the only nation where medical bankruptcies exist.

But really the meta-problem of this chart, and also what is so irritating about many degrowth critiques in general, is that we have a well-known paradigm for thinking about reducing resource and energy consumption without sacrificing end goals.

The Catalytic Society

A catalyst is something that increases the rate of a chemical reaction. Catalysts work by enabling alternative pathways that differ from the uncatalyzed reactions. These pathways lead to the same products while having lower activation energy.

Read that again: Catalysts work by enabling alternative pathways that differ from the uncatalyzed reactions. These pathways lead to the same products while having lower activation energy.

Golly, that sure sounds like Degrowth!

And using this framing, it is clear that degrowth is not anti-innovation or anti-technology. Catalysts are a form of innovation and technology! Nor does degrowth aim to reduce living standards; the whole point of a catalyst is to achieve the same outcome with less energy. Nor is degrowth anti-growth; that would be an inhibitor, not a catalyst.

Perhaps most importantly, this framework also provides an opportunity to rid Degrowth of its truly horrendous name, which, in English, implies all these misguided things, even though they aren’t necessarily part of Degrowth. So from now on, I’ll use Catalysis.

Now, a Catalytic society would certainly be different than our current one. Possible changes range from fairly innocuous to truly radical with an entire spectrum in between. But I think that most people radically underestimate how much proverbial fat could be trimmed without sacrificing quality-of-life. There are ‘radically-moderate’ versions of Catalysis/Degrowth with washing machines1 and bananas (to use two famous prescriptive examples that I’m not even going to link to because they are dumb).

Degrowth Without Change: The Catalytic Ethic

“It will take some time before people recognize that the project… is neither nostalgic nor utopian but rather the realistic sort of occupation anyone can participate in every day that has an immediate and practical chance of curbing our present waste and recklessness.” - Kirkpatrick Sale

Transportation produces ~30% of total US greenhouse gas emissions. Over the last fifty years, total vehicle miles traveled (VMT) has increased at a fairly constant rate, growing to ~3.2 trillion miles in 2023. This consumed ~135 billion gallons of gasoline.

While gasoline consumption enables much of “the economy,” it is also widely recognized as a input cost. Multiple efforts, such as increasing fuel-efficiency standards, improving the aerodynamics of vehicles, and converting the fleet to EVs uptake, have been made to decrease our gasoline consumption. These efforts have combined so that we currently consume about the same gasoline as in 2002, despite more VMT.

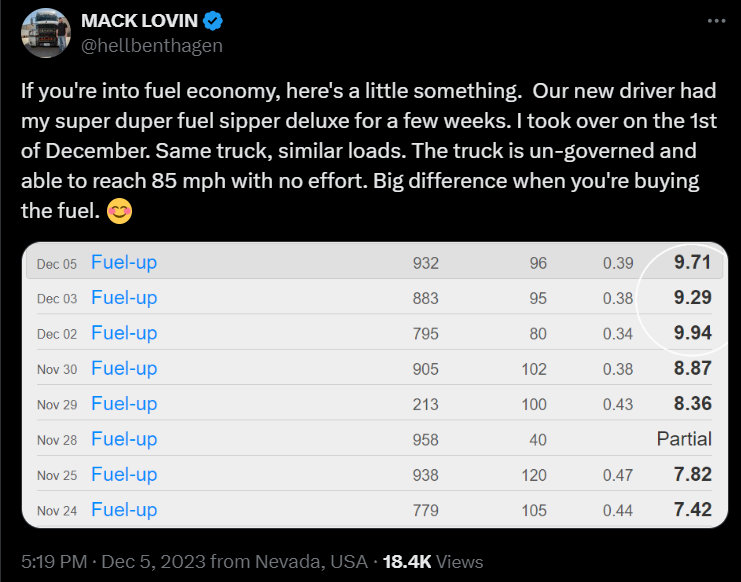

These efforts are good and should be applauded. But the United States could immediately decrease our gasoline consumption by over 10%, without a single change in our vehicles or total VMT. How? With fuel-efficient driving techniques.

Fuel-efficient driving is achieved by: stop aggressive driving (reduces fuel efficiency by over 10%), accelerate lightly and steadily, drive ~50 mph when safe, inflate tires properly (increases fuel efficiency by ~0.6%), reduce unnecessary weight in the car (an extra 100lbs in your vehicle reduces your MPG by about ~1%), learn to anticipate and coast toward lights, stops, turns, and traffic, and several other techniques.

And while the primary purpose of this is to decrease fuel consumption, it should also be noted that it also saves both brakes and tires, which are major causes of air pollution and environmental microplastics. Moreover, decreases in speed and aggressive driving would result in fewer accidents, meaning less cars and car parts produced, as well as a smaller insurance industry, and most importantly, human lives would be saved.

A culture of fuel-efficient driving would lead to significant reductions in fuel consumption, air pollution, environmental microplastics, and decrease the size of the fossil fuel, automobile, healthcare, and insurance industries. Yet it would undoubtedly improve our society, and could be achieved without a single vehicle converting to EV, any reduction in total VMT, building more public transportation, or changes to fuel efficiency standards (all of which great things that we should aim for separately).

Obviously, this would require a widespread cultural “change,” and we shouldn’t expect absolutely everyone to do it. But history is littered with much larger examples of widespread cultural change: the shifts from hunter-gathering to agricultural, small tribes to nations, polytheism to monotheism, autocracy to democracy, patriarchy to women’s rights, slavery to human rights, the reduction in the smoking rate.

And once you start looking for examples like this, where we use resources and energy frivolously and wastefully, and whose consumption could be curbed with simple cultural changes, you’ll start seeing them everywhere.

Agriculture accounts for ~10% of US greenhouse gas emissions. We waste ~30% of our food.

Buildings, both residential and commercial, account for ~40% of total US energy consumption, much of which is HVAC. Large reductions in this energy consumption could be achieved with a culture of “heating people, not places.”

Apparel and footwear is ~10% of global emissions. The vast majority of adults would be perfectly fine if they didn’t purchase any additional clothing or shoes over the next year. Obviously, new clothes would have to be purchased eventually, but we could build a culture of buying high-quality clothes (not fast fashion), repairing them rather than throwing them away, and (true) recycling or re-using them when their lifecycle is complete.

Light pollution not only wastes energy, but also impacts both human and ecosystem health. Next time you’re outside after dark, try to notice all the lights that could be turned off or reduced with no impact. They’re very easy to spot once you start looking.

Ultra-cold freezers are critical for scientific research. By convention, their standard temperature is -80C. But increasing their temperature to -70C has been shown to not compromise sample integrity, while reducing their energy consumption ~10-30% while also extending the life of the freezer.

My favorite hyper-niche example: Maryland places a separate highway sign that names the current governor at every major entrance to the state. Think of the time, energy, and material used to change these signs every ~4-8 years.

Now, think about this seriously before answering. Let’s assume that the majority of people got serious about these and other changes and started living a “reduce, reuse, recycle” lifestyle. Say we reduced the United States’ total resource and energy consumption by ~10%. Would that be bad? Of course not. People aren’t obligated to consume. If people simply decided to consume less, be more frugal, save more, spend time and energy on less-resource-intensive areas and projects, how could that be bad?

Yet if this actually happened, it would crash the economy. Because we’ve built a economic system whose foundation is continuous and perpetual growth. Now, something I think that Degrowthers often fail to recognize is that we developed that system for very good reasons. For the vast majority of human history, we were utterly and desperately poor, a single bad season away from famine, a single act of God away from pestilence. We genuinely did just need raw growth, and the spillover from that growth was a rising tide that lifted all boats.

But just because something a strategy worked in the past, doesn’t mean it is the optimal one for the future. Much has changed; we aren’t the desperately poor people that we once were. Perhaps we need to rethink and redesign our institutions and economic system. And if individual people aren’t obligated to consume, perhaps neither should our larger system.

Degrowth With Change: Structural Catalysis

Every autumn, pictures of Vermont’s fall foliage circulate online and everyone admires its beauty. Who doesn’t love cozy small towns nestled into valleys and mountains covered in swirls of fall colors?

But what you might’ve not noticed is the complete absence of billboards. Vermont has completely banned them, along with Maine, Hawaii, and Alaska.

Are the “economies” in these four states smaller because of this? Of course. Not only do they lose the direct activity of building, operating, and maintaining billboards, but also the indirect activity that those billboards would generate.

But they’ve also gained something, even if it doesn’t have direct “financial value:” the beauty of an uncorrupted environment.

Catalysis/Degrowth correctly points out that advertising is a form of mental and environmental pollution. Have you ever been at the beach on a beautiful, calm day that was interpreted by an airplane flying a banner for a local business? Have you ever been frustrated trying to read a web page page that constantly jumps from loading advertisements? Are you tired of the constant stream of advertisements for alcohol, gambling, and politics on television? How large is the pile of junk mail that you receive and discard each week?

Most people understand that pollution creates negative externalities, and that a polluter makes decisions based only on the direct cost of and profit opportunity from production and does not consider the indirect costs to those harmed by the pollution. Fortunately, we could regulate so that less or none of that pollution occurs.

The quintessential example is direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising, a practice that is legal only in the United States and New Zealand. Pharmaceutical companies spend ~$6B per year in advertising in the United States. A recent study published in JAMA found that higher direct-to-consumer spending was associated with higher total drug sales and lower clinical benefit ratings.

Think about that: we could make DTC pharmaceutical advertising illegal overnight, it would save us ~$6B in healthcare expenditures,

Just like with the bottom-up cultural changes, once you start looking for examples, you’ll see them everywhere:

Buildings: require passive solar design in our building codes,

Macro-urban planning: abolish single family zoning in major metros, especially in climate resilient areas such as the coastal West Coast and the Great Lakes. For example, Los Angeles could add ~1.5 million housing units by up-zoning just Wilshire Blvd.

Micro-urban planning: disincentive golf courses and self-storage centers

Agriculture: incentivize subtle urban permaculture through requiring the planting of tree and shrub crops in new developments, parks, and tree planting projects, while large-scale agricultural policy could shift away from industrial monocultures and CAFOs (that are only possible because of cheap fossil fuels) to agroecological techniques like agroforestry or silvopasture and multi-species rotational grazing.

Aviation: the majority of Americans don’t fly a single time in any given year. We could curb aviation emissions through a progressive frequent flyer tax.

Transportation: improve and build out better public transportation systems, like subway and metro systems in densified cities, high-speed rail between major cities in our megaregions, protected bike lanes and frequent bus, congestion pricing in major metros for all private vehicles

Energy policy: nuclear energy, both building more current fission technology and investments in developing fusion technology

Taxation: implement progressive carbon taxes and consumption taxes on physical goods

My favorite niche example: regulate away items whose purpose is littering like glitter, confetti, and fireworks.

Yes, some of those changes are large. But society has made large changes before and large will be necessary to address our ecological crisis, where we’ve made shockingly little progress on many of its variables, while the “power laws” of emissions and consumption are steep. But large paradigm shifts don’t happen overight, and we should have no expectation that building a Catalytic society will be easy.

Implementing Catalysis

“As soon as a society recognizes that it cannot maximize everything for everyone, it must begin to make choices. Should there be more people or more wealth, more wilderness or more automobiles, more food for the poor or more services for the rich?” - Donella Meadows

While many people will probably be sympathetic to grassroots, voluntary efforts to reduce resource and energy consumption, many people will also be wary of top-down, paternalistic efforts that work to achieve this at the societal level. How and who will we decide which sectors and projects are worthy of resources and energy?

The quintessential example of this conflict is probably the recent investments in space travel by billionaires such as Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Richard Branson. Many people insist they are frivolous uses of time, energy, and resources that could be spent on improving things here on Earth. Others insist they are worthwhile because of the direct technological advances they’ve provided, potential technological developments such as asteroid mining, or philosophical reasons such as “hedging our bets” by making humanity multi-planetary.

The thing to recognize is that we already have to make top-down decisions every day: which projects receive investment funding, which industries receive subsidies, what are types and rates of taxation, which federal, state, and local agencies are awarded contracts, grants, and funding, etc. “What should we collectively do with our resources, energy, and labor?” is a question that we already answer!

Catalysis isn’t really asking anything new, so much as a re-framing and re-prioritization of the answers. Rather than focusing on “GDP growth” or “return on investment,” it suggests we should focus on projects that prioritize outcomes like “human/ecosystem well-being” or “energy return on investment” or “community sufficiency.”, It’s a society that builds public transportation, not endless “one more lane will fix it” highways.

And even in a completely “free market,” there are still strings attached to market decisions: the cost of capital, constraints on time and labor, etc. When the Federal Reserve raises or lowers interest rates, that affects where investment flows and which projects get funded. This is most clearly articulated by the term “ZIRP phenomenon” that arose during the 2010s to describe projects only possible because of a decade of zero interest rates.

Yet again, Catalysis isn’t proposing anything new, just a re-framing and re-prioritization of our current system. Rather than maniacal focus on financial returns, we should start factoring in energy and human well-being returns. And if our society decides to “raise the cost of energy” (rather than capital), then yes, certain low energy-return projects won’t be started, just like low financial-return projects aren’t started when interest rates are high. Somewhat more expensive energy doesn’t leave us in poor house (especially if consumption taxes are implemented progressively), but shifts us toward true efficiency (not Jevon’s paradox efficiency) that concentrates the energy we continue to consume on the highest leverage activities.

In fact, many of the ‘low-energy’ aspects of life are what we value most: family & friends, care, education, leisure, recreation, etc. Again, no serious person is proposing that we return to a hunter-gather lifestyle with certain ‘high-energy’ activities like healthcare. Modern healthcare is a miracle that we should keep. But mega-yachts and private jets aren’t healthcare. Pickup trucks the size of tanks aren’t nutrient-dense food. Mega-mansions with infinity pools go beyond shelter.

A ‘market-based,’ democratic Degrowth is possible, where there is large-scale feedback between a grassroots, bottoms-up cultural ethic and common-sense, top-down politics, where investment is channeled away from economic growth at-all-costs, into primarily areas, projects, and ideas that have high returns on quality-of-life per energy. Where there is balance between growth and sufficiency, the environment, and justice for all.

Why Catalysis?

While I haven’t covered absolutely everything I’d like to, this is getting long, so let’s quickly wrap up with two final sections.

Why do we need Catalysis? What are the advantages?

First, it helps with many of modernity’s problems. Widespread Catalysis would improve many aspects of our polycrisis: obviously ecological overshoot but also biodiversity loss, rising geopolitical conflict, cultural erosion, economic inequality, accumulating financial debt, etc.

It also buys time for technological innovation. If you’re saving money for something, the best strategy is to both increase income and decrease spending. Technology has allowed us to increase our ‘societal income’ but in many ways we are “keeping up with the Jones” and just living paycheck-to-paycheck given the long-term ecological damage we are causing. Nuclear fusion would be an incredible achievement, and something we should invest in, but it’s always a decade away, as they say. Let’s assume that Catalysis curbs emissions by ~25%, that buys a huge amount of time for us to develop game-changing technologies.

It also provides a buffer against tipping points. A tipping point is a critical threshold that, when crossed, leads to large, accelerating and often irreversible changes in the climate system. One that is getting recent attention is the likely eventual AMOC collapse. There is uncertainty around when these tipping points will be reached, but toning down our emissions through decreased resource and energy consumption gives us extra cushion before we reach any.

Global justice and fairness is another important aspect to Catalysis. It is not well understood how much poverty still exists in the world. These billions of people deserve improvements in their quality of life. But if “quality of life” is understood as “current consumption levels of Americans,” we will roast the biosphere. How else can we reconcile the two facts that ~50% of all emissions ever produced have occurred in the last 40 years and ~7 billion people still live on less that $30 per day?

Finally, it would be a better world: imagine if we weren’t endlessly cluttered and overwhelmed with stuff, if we had fewer things, but they were high-quality and meaningful. Imagine local, more nutrient-dense food that leds to fewer health problems and synthetic chemical use. Imagine high quality clothing made from natural fibers that we repaired and grew with over decades. Imagine cleaner air and clean water and healthier soils because we see ourselves as stewards of nature, rather than masters of it. Imagine be unsaddled from expensive car payments and repair and insurance, where the no-brainer decision is the inexpensive monthly public transit pass. Imagine neighborhoods that are walkable and teeming with life and relations, villages of dense, mixed-use developments and local businesses. What if instead of accumulating goods, we accumulated friendship and leisure and care and education? What if instead of subsidizing fossil fuels and petroleum products, we built nuclear power plants and emphasized natural products? Etc. Etc.

A Positive Vision of Catalysis

My favorite vision of Catalysis/Degrowth in media is the semi-famous ‘solarpunk’ Chobani commerical.

Now, it would be somewhat of a cop-out if I ended a piece of fictional media, however great it may be.

But we’ve already discussed five countries who use half of the energy per person of the United States. All of these places are nice to live, but let’s focus on France.

Every year, millions of people visit France for its charm, beauty, history, and food. Paris is one of the preeminent global cities and roughly the same geographical size as San Francisco, yet has ~2.5x the number of people, mainly because it builds mixed-use multi-story buildings. It has seen huge reductions in air pollution by cracking down on cars while building out public transportation, while its GDP and emissions have decoupled, in large part because of widespread nuclear power. There food is obviously amazing and they enjoy more vacation time per year than us. Yes, they are so centralized that in order to take the train from Bordeaux to Lyons, you have to go through Paris, yet it is still faster than driving. With the downfall of Boeing, they also have the best aerospace company in the world.

France is obviously not a perfect place, but it has a very high quality-of-life, and to repeat, they consume half of the energy per person of the United States.

To end, I believe in the United States and I believe in humanity. We can build a world not centered around growth and consumption and in the process, catalyze a better world for all.

To really emphasize how stupid the washing machine take was, if we really were going to get rid of one machine in the laundry room, it would be the dryer, which uses more energy than a washing machine, and has easier-to-implement and more-culturally-known replacements: the clothesline and the drying rack.

An environmental science teacher I had in university called it "regrowth" and was extremely angry at the coopting of environmentalism by literal primitivist de-growthers. I held a lot of respect for him because of that, as he was focused on reducing the price/improving the efficiency of renewable energy production, rather than "just ban oil" or something terrible like that. He essentially framed it as a pursuit of higher quality and efficiency over quality.

There's a lot of thought and effort that went into this more moderate approach. Unfortunately, I think it misses a key point about capitalism. Companies need to have growth year after year to retain investors, keep up with inflation, and line the pockets of its employees and owners. But at some point, Facebook is done. The website is completed, algorithm finely adjusted, and everyone has adopted it. The fact is, healthy businesses achieve their goal and just need to coast. They don't need to grow, they need to divest, reduce staff, and downscale. But you can't do that in capitalism, so the only other way is to vertically and horizontally integrate...which leads to monopoly. Monopoly, the end product of thorough capitalist competition.