We Have Become Death, Destroyer Of Fences

Some thoughts on Chesterton's Fences, modernity, and AI.

The Counterpoint is a free newsletter that uses both analytic and holistic thinking to examine the wider world. My goal is that you find it ‘worth reading’ rather than it necessarily ‘being right.’ Expect semi-regular updates and essays on a variety of topics. I appreciate any and all sharing or subscriptions, as it helps support both my family and farm.

G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) is one of those people who really make you appreciate the full spectrum of humanity. He was a literary critic, historian, novelist, playwright, theologian, and social commentator. With an acerbic wit, razor pen, and clear-throated morality, he rose to the top of the European intelligentsia by writing dozens of books, hundreds of short stories, and thousands of essays on just about any topic imaginable, ranging from mystery novels and British geopolitics to economic systems and a biographies of St. Francis of Assisi and St. Thomas Aquinas. His book ‘The Outline of Sanity’ was one of the ten best books I read in 2023.

Perhaps most importantly, he looks exactly as a 19th-century British mad genius should look.

One of his concepts that has some level of infamy but should be more well-known is that of Chesterton’s Fence. To quote him specifically:

There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

To put it concisely: do not remove a fence until you understand why it was put up in the first place.

The lesson is that what already exists (be it a fence, law, social convention, or something else) likely serves purposes that are not immediately obvious, and that problems arise when we intervene on systems without an awareness of what the first-, second-, and third-order consequences will be. Even if we are well-intentioned, it is easy for rashness to do more harm than good. If a fence exists, it is likely there for a reason.

There has been much written on modernity: the exponential growth of industrialization, technology becoming increasing ingrained in human life and society, the expansion of democracy and human rights, etc., etc. But perhaps a foundational part to modernity’s psyche is a general disregard for Chesterton’s fences.

The foremost and ongoing example is the Trump administration, Elon Musk, and DOGE.

Musk and DOGE are currently dissembling broad swathes of the federal government. They claim that they are doing to combat waste, fraud, and corruption, and maybe many of these programs are useless, costly, dumb bureaucratic “fences” that should be dismantled. But Chesterton’s fence isn’t saying that all fences have uses, only that some do, and that it can be very hard to distinguish between them. So you understand which type of fence it is before you knock it down.

And it’s quite clear that DOGE is just blindly dismantling programs, many of which are the useful type. If you’ve been following any of the reporting on this, it’s not marginally useful programs either, but really quite unarguable, outright great programs getting revoked and ended.

There really is the pick of the litter here1, but I’ll highlight two in particular.

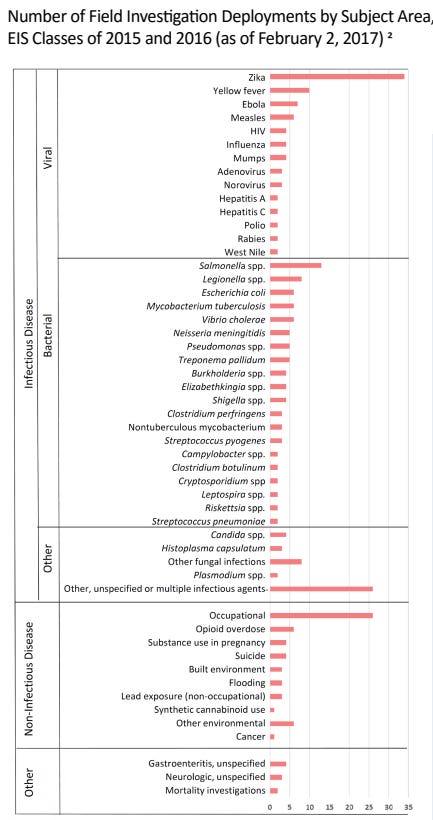

First, last Friday, many members of the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service received news that they’d be dismissed. Established in 1951, the EIS is a two-year fellowship for applied epidemiology. They are literally medical detectives deployed any time there is an outbreak of mysterious illness. For example, they were critical to the United States’ response to the Zika outbreak in 2016 (case numbers for all field investigations that year shown below). And it’s not just infectious disease; for example, they helped figure out that it was Vitamin E acetate in tobacco and cannabis vapes that was causing an outbreak of lung injuries across the United States.

Can you think why it might be good to have a team of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Houses on staff at the CDC that can be rapidly deployed to various medical mysteries around the country? Can you see why that might be a good “fence” to maintain?

Second, consider the cuts at the Department of Education. DOGE has bragged about terminating 89 contracts worth a collective $881 million at the Institute for Education Sciences at the US Department of Education. Stuart Buck at The Good Science Project has an excellent piece on some “inexplicable” cuts that have been made. He writes, “none of the above is wasteful, or “woke,” or anything else that would be objectionable to 95% of Americans.” Below is a screenshot of some:

Can you think why it might be good to have long-term, cross-state, longitudinal studies on various aspects of our educational system? Can you see why that might be a good “fence” to maintain?

Now, I started with the current administration and DOGE because it’s ongoing and one of the topics de jure, but in retrospect, this disregard for Chesterton’s fences seems to have been foundation to the Left’s response to the pandemic.

I think that many people have memory-holed the severity of the early pandemic. There was a novel pathogen ripping through New York City with such intensity that hospitals were storing bodies in refrigerated trucks. In a world where people are increasingly institutional sclerosis, I think it’s incredible that the globe tried “lockdowns,” even if I’ve also written that they could’ve been done better with a slight modification. There was a severe situation and we tried something new.

But also we moved into the second half of 2020, a partisanship developed, and red states started quickly loosening restrictions while blue states retained them. And while the exactly timelines are debatable, by 2021, it is now clear that the refusal to re-open schools and increasingly rely on online education resulting in “learning loss” for many across any entire generation. And beyond the educational, the cancelling of traditions like homecoming and graduation, as well as just everyday, routine socialization, really affected children and adolescents.

It should’ve been recognized sooner that the “fences” of in-person education, socialization, and school traditions are a genuine part of childhood and adolescent development.

Moving on to something non-political, it is literally Silicon Valley’s motto to “move fast and break things” (read: break fences). And sometimes, it’s a genuine improvement to society. But often, it’s also just rapid disruption and breaking of critical parts of life and culture.

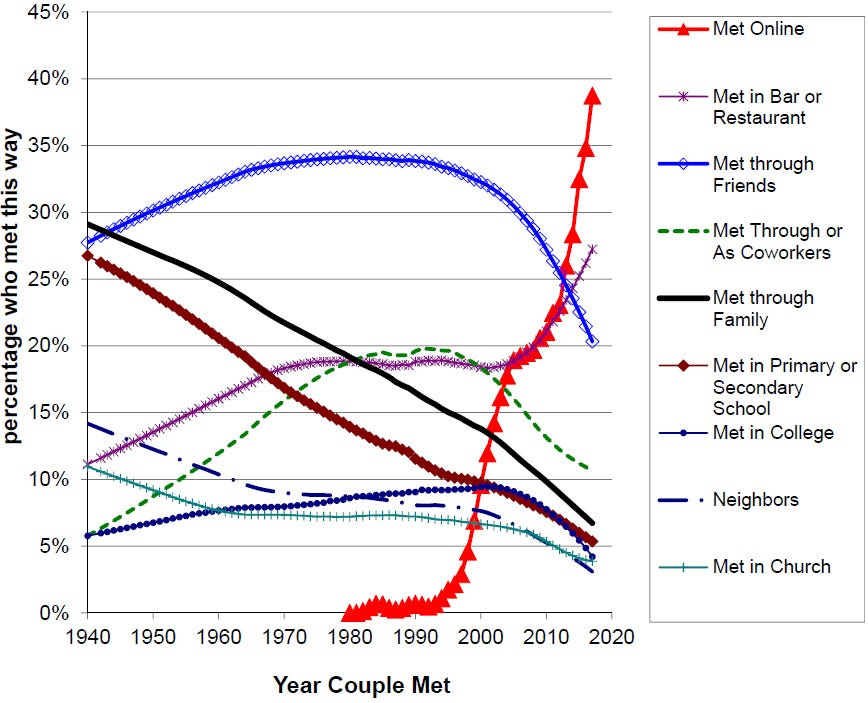

Consider how people now start romantic relationships. After literal millennia of meeting people in-person through various routes, within a generation it has become majority online (below).

Don’t you think that might change some things? How it might be contributing to continued declines in marriage? Or changing relationship dynamics to the point that ~45% of young men have never approached a woman? Or the rise of the “Incel” movement?

Take the smartphone: using Google Maps to get around town is great and helpful, but it also appears to reduce our navigation abilities.

This is only a minor example where we might genuinely take that tradeoff, but there is growing recognition that introducing smartphones and social media have contributed negatively to childhood and adolescent health and well-being. Jonathon Haidt’s “The Anxious Generation” (whose graphs and figures can be found here) is one of many texts and studies that compelling suggest that we, as a society, have just ignored the “fence” that children need to go outside and play with each other to develop properly.

The Ultimate Chesterton’s Fence

Often the development of true artificial intelligence is told as an apocalyptic dystopia: the AI triggers nuclear warfare, harvests our bodies for heat and processing power, develops an unstoppable bioweapon, or sends a cyborg assassin back in time to kill the future leader of the resistance.

Yet I recently came across a paper that unsettled me more than any of these apocalyptic dystopian ones. Bad scenarios are easy to craft and understand. But what if the development of true artificial intelligence goes, well, too well? What if that apocalyptic future is actually a utopia, where a wrecking ball is taken to the ultimate Chesterton’s Fence.

The entirety of human civilization centers around human agency and applying it to achieve goals. What happens if AIs continue to steadily improve, leading to a multipolar trap, where more and more of the economy, life, and culture is ceded to them, slowly leading to a “gradual disempowerment” of humans? What if the end state of human civilization isn’t a bang, but a whimper?

The aforementioned piece is “Gradual Disempowerment: Systemic Existential Risks from Incremental AI Development” by Jan Kulveit, Raymond Douglas, Nora Ammann, Deger Turan, David Krueger, David Duvenaud. (executive summary here, full paper here).

The full paper (26 pages) is very much worth the read but an extended quote from the executive summary that summarizes the argument well is below:

AI risk scenarios usually portray a relatively sudden loss of human control to AIs, outmaneuvering individual humans and human institutions, due to a sudden increase in AI capabilities, or a coordinated betrayal. However, we argue that even an incremental increase in AI capabilities, without any coordinated power-seeking, poses a substantial risk of eventual human disempowerment. This loss of human influence will be centrally driven by having more competitive machine alternatives to humans in almost all societal functions, such as economic labor, decision making, artistic creation, and even companionship.

A gradual loss of control of our own civilization might sound implausible. Hasn't technological disruption usually improved aggregate human welfare? We argue that the alignment of societal systems with human interests has been stable only because of the necessity of human participation for thriving economies, states, and cultures. Once this human participation gets displaced by more competitive machine alternatives, our institutions' incentives for growth will be untethered from a need to ensure human flourishing. Decision-makers at all levels will soon face pressures to reduce human involvement across labor markets, governance structures, cultural production, and even social interactions. Those who resist these pressures will eventually be displaced by those who do not.

Still, wouldn't humans notice what's happening and coordinate to stop it? Not necessarily. What makes this transition particularly hard to resist is that pressures on each societal system bleed into the others. For example, we might attempt to use state power and cultural attitudes to preserve human economic power. However, the economic incentives for companies to replace humans with AI will also push them to influence states and culture to support this change, using their growing economic power to shape both policy and public opinion, which will in turn allow those companies to accrue even greater economic power.

Once AI has begun to displace humans, existing feedback mechanisms that encourage human influence and flourishing will begin to break down. For example, states funded mainly by taxes on AI profits instead of their citizens' labor will have little incentive to ensure citizens' representation. This could occur at the same time as AI provides states with unprecedented influence over human culture and behavior, which might make coordination amongst humans more difficult, thereby further reducing humans' ability to resist such pressures. We describe these and other mechanisms and feedback loops in more detail in this work.

Though we provide some proposals for slowing or averting this process, and survey related discussions, we emphasize that no one has a concrete plausible plan for stopping gradual human disempowerment and methods of aligning individual AI systems with their designers' intentions are not sufficient. Because this disempowerment would be global and permanent, and because human flourishing requires substantial resources in global terms, it could plausibly lead to human extinction or similar outcomes.

Every twenty years, locals tear down the Ise Shrine in Mie Prefecture, Japan, only to rebuild it. They have been doing this for ~1,300 years. The process of rebuilding the wooden structure every couple decades helps to preserve the original architect’s design, but more importantly, against the eroding effects of time, both physically and culturally. Both structural pieces and artisanal skills are renewed in each generation of rebuilding. The Long Now Foundations writes, “It’s secret isn’t heroic engineering or structural overkill, but rather cultural continuity.”

Now compare that to a recently-published study by Microsoft on the changes in critical thinking skills of engineers who use current “GenAI” technologies. To quote the study, “higher confidence in GenAI is associated with less critical thinking, while higher self-confidence is associated with more critical thinking.”

Now, no single study is ever definitive (you can read Erik Hoel’s thoughful thoughts on it here), but other studies have also found “skill decay” from technological use. And consider three important aspects of the Microsoft study:

the Microsoft engineers in this study are some of the highest agency and most intelligent people

current GenAI technologies are likely exponentially less capable than they will be in the future

the current GenAI technologies touch exponentially fewer aspects of human life than they will in the future

Synthesizing this all together, it is hard not think that there will be widespread “skill decay” or “human disempowerment” once companies start releasing ever more powerful AIs that touch more and more aspects of human civilization to the general population.

What is especially toxic and undermining is that this won’t happen overnight. Compounding returns are often underestimated by humans due to the short-sightedness and immediate survival needs breed into us through millions of years of evolution. Albert Einstein remarked that “compound interest is the eight wonder of the world,” yet many Americans find it difficult to save enough for retirement.

So what happens if reduced interactions with human beings cause social skills to corrode 1% per year or if the skills of AI-reliant physicians decay by 1% per year? If governments depends on taxation of the AI economy by 1% more each year? If pornographic texts and videos gets 1% more appealing each year? What happens to attention spans and psychological fortitude if the AIs get 1% better each year at giving you exactly what you want exactly when you want it? What happens if ‘Nigerian Prince emails and crypto scams get 1% more convincing each year?

It won’t take long until the Chesteron’s fence of human agency being the foundation of civilization is gone.

The Meta-Ultimate Chesterton’s Fence

Don’t get me wrong, the undermining of the entire economic, political, cultural, and social structure of human civilization is, in a word, bad. But there is an even deeper and more sinister philosophical problem that we as a species have yet to reckon with in regards to artificial intelligence.

I’ve written about becoming a father and it has been fascinating watching my daughter mature through toddlerhood. Every day, her awareness and sense of the world and language grows. Slowly but surely, she is becoming her own person, and I know that this will eventually lead to interpersonal conflict between us as our goals and ideas won’t always align. But she is still human.

The Meta-Ultimate Chesterton’s Fence is that humans are the only intelligence on Earth. The development of a true artificial intelligence(s) means that there are now literally other intelligent agents on Earth. This will require us to full-stop confront the reality of staring into the abyss of The Other.

I don’t think we’ve even begun to reckon with this reality. So much of everyday basal human life and civilization depends on the reality that every agent we encounter is a human, and that we all have some conception of and empathy toward each other. This is one of those David Foster Wallace ‘This Is Water’-type things; we don’t even notice it. Even when dealing with psychopaths (people unable of feeling empathy), at least at some level they still feel physical pain, emotional angst, the pangs of hunger.

What happens when companies and governments just start injecting non-human agents into the world? What happens when they begin behaving in novel ways that we can’t predict? What happens if robotics and prosthetics develop so robustly that it becomes almost impossible to distinguish AI from human, a Westworld over the entire planet? What happens when they develop the capacity for deception?

To put it cheekily, have you ever heard the adage, “if you can't spot the sucker at the table, then you are the sucker.” Well the development of true artificial intelligence would make us the sucker at every table. And that might be all fun and games when that novelty is an interesting Go move, but what happens when it touches nearly every aspect of human life?

In the Hyperion Cantos series by Dan Simmons (warning: mild spoilers), humanity has developed into a near-utopia. The AIs have developed technologies, such as faster-than-light travel, that caused a new level of human flourishment. Yet it is slowly revealed that the AIs have their own goals and have been manipulating, non-maliciously, humanity to their own ends. It is a vampiric deception; they’ve caused our flourishment only because it allows their own parasitism to grow.

That’s the thing; deep down we already know that we can’t fully trust other minds. But at least we’re bounded by millions of years of pro-social evolutionary development. At least we all have the same neurotransmitters and hormones and pain receptors that guide us to, very roughly, the same goals and desires. But artificial intelligences will have none of that, and their intelligence and speed and processing power will be cranked a million times (or more) higher than ours.

How will we and society change when not only are there millions of HALs everywhere, but we know there are millions of HALs everywhere, and they know that we know. Not only does the ‘chess game’ of life suddenly becomes infinitely more complex, but more importantly, we can never be sure of the other player’s peices.

I’m going to end it here because I’m not even sure if I’m making much sense. I feel like I’m rambling, an old man shaking his fist at the clouds.

But the “gradual human disempowerment” thesis has deeply unsettled me, usually the perennial optimist, in ways that I haven’t been able to shake. It makes me want to retreat to my farm and forget about the world. At least there, I can promise that I won’t be tearing down any fences without understanding their purpose.

To name a few:

the firing of hundreds of workers involved in the maintenance of the nuclear arsenal

the firing of hundreds of workers at the Federal Aviation Agency

the ending of the PEPFAR, a program which has saved ~25 millions lives

Senator Ted Cruz released a list of ~3,400 NSF grants, representing ~$2B in funding, “toward questionable projects that promoted DEI or advanced neo-Marxist class warfare propaganda.” Scott Alexander of Astral Codex Ten reviewed them and found that ~60% weren’t “woke” at all.

The administration economic strategy appears to be what Kyla Scanlon calls “FAFO economics”

I've been thinking about Chesterton's fences a lot lately, too, and the overall de-skilling of humanity. It's one reason it bothers me so much when the left, supposed opponents of capitalism, say you shouldn't "be productive" in your time outside of paid work. I think they fail to understand where that feeling comes from, why we feel bad (though clearly some of us worse than others) when we're unproductive. This isn't to say there should be no leisure time, because I don't believe this, but I take the admittedly old-fashioned view that your leisure time should be mostly about the development and exercise of skills -- mental, physical, and social -- and as little as possible spent in passive consumption. Even saying this in public, I feel a little anxious that people will think me kind of an arrogant jerk. Idk, maybe I'm an arrogant jerk, so be it.