Adopt-A-Tree On Blue Glade Farm

Directly support a small farm's transition to agroforestry and silvopasture, two ecological forms of agriculture.

The Counterpoint is a free newsletter that uses both analytic and holistic thinking to examine the wider world. My goal is that you find it ‘worth reading’ rather than it necessarily ‘being right.’ Expect semi-regular updates and essays on a variety of topics. I appreciate any and all sharing or subscriptions, as it helps support both my family and farm.

There is much to say about our modern industrial agriculture and food system1. For now, I will simply say two things:

First, it has done an excellent job at solving the primary problem that an agricultural system should: “feeding the world.” We have made extraordinary progress at reducing hunger and malnourishment, while famines have almost been eliminated.

Second, it has numerous and significant negative externalities, many of which are unsustainable: its grossly dependent on fossil fuels and synthetic chemicals, it emits large amounts of greenhouse gases (and not just carbon dioxide), is often cruel toward its animals, causes topsoil loss, destroys biodiversity and wildlife habitat, pollutes our water and air, and prioritizes calories over nutrition.

In our current system, over 80% of all harvested calories come from just ten crops, almost all of which are annuals. Moreover, the top three crops (corn, rice, and wheat) are all specifically annual grains and together account for ~50% of all food calories.

That our agricultural system evolved around annual grain crops makes sense: you plant a seed in the spring, harvest the calorically-dense crop in the fall, and it’s easily storable for winter. This sets up a positive feedback loop of survival → iterative breeding → higher crop yields → survival that caused the agricultural evolution and, well, all of civilization.

While this was critically important for humanity when we were only a single bad season away from famine, there is growing recognition that the priorities of the modern system need to shift to ensure not only our immediate caloric needs, but also the long-term sustainability and resilience of the system itself. Now that we've solved the caloric problem, the agricultural question of our age is how do we solve the nutrition, sustainability, and resilience problems, while continuing to meet caloric needs.

Part of that answer is that we need more trees.

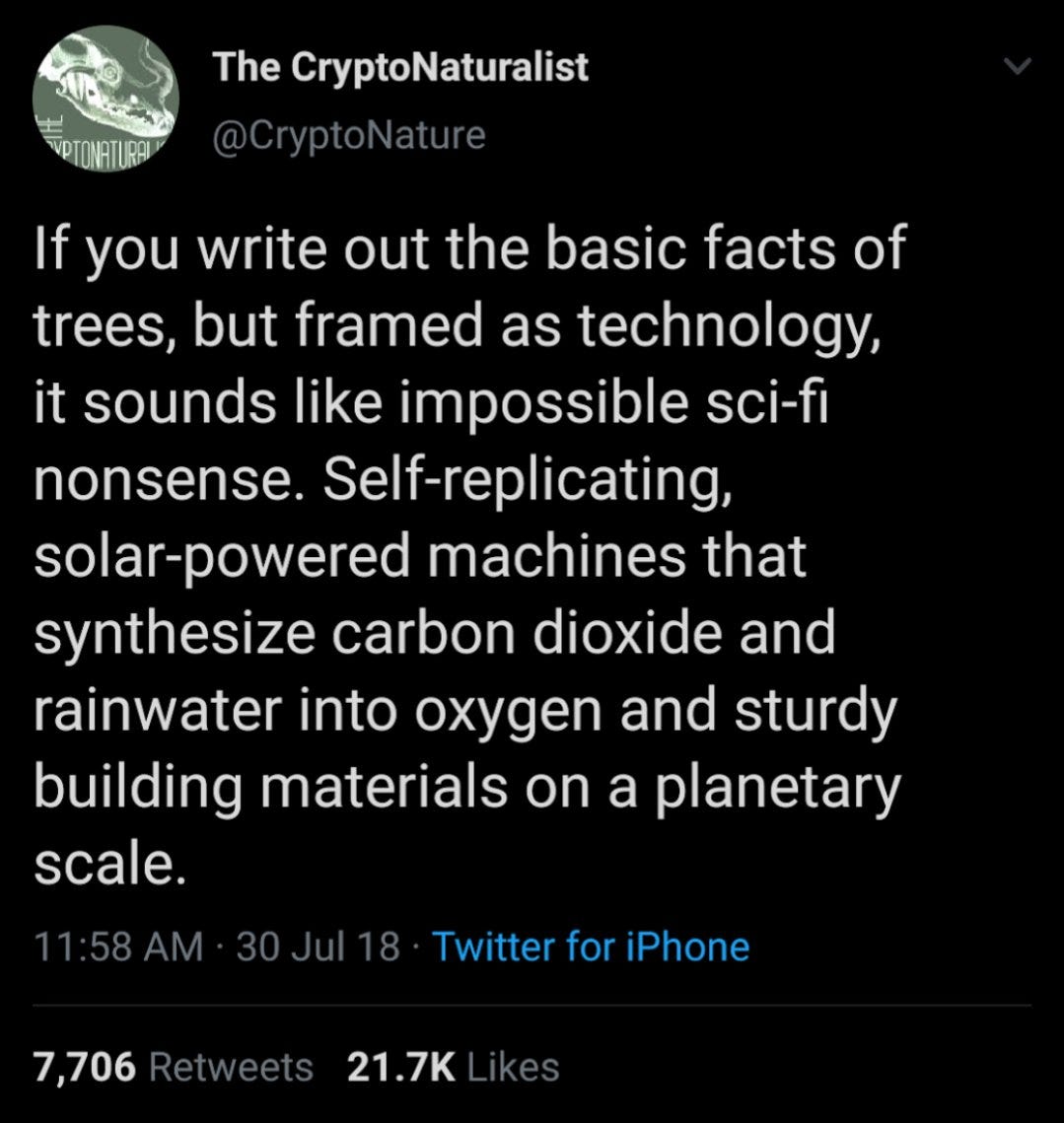

Trees are nearly a panacea: in addition to producing food, firewood, and eventually lumber for building materials, furniture, and various other miscellaneous items (e.g. white oak for whiskey barrels), they provide incredible valuable ecosystem services: they reduce temperatures in both urban and natural environments, prevent soil erosion, capture nutrient runoff, increase wildlife habitat, protect biodiversity, create rainfall, sequester carbon, and synthesize oxygen, all while being “solar powered.”

With respect to food production, trees are also perennial species. Unlike annual grains, once a tree is planted, it will stand and produce for decades, centuries, and even millennia (there are olive groves that are ~4,000 years old and a chestnut tree that is ~3,000 years old). While industrial grain farmers are required to burn fossil fuels every single spring preparing their fields, planting their crops, and spraying synthetic chemicals, you can plant a chestnut once, by hand with a shovel, and it will stand and produce an annual crop for several centuries.

But trees have one major downside: they grow slowly with many years before the first harvest. If you plant a chestnut today, you won’t have your first nut for ~5 years, significant harvests for ~10 years, and fully mature harvests for ~20 years. There are reasons we have proverbs like, “one generation plants the trees, and another gets the shade” and “a society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they shall never sit.”

The nature of this extremely-long-term investment places tree crops at odds with the short-term financialization of modern society and agriculture. What bank would lend you money for an asset that won’t produce revenue for a decade? What farmer would transition acreage to trees when they have mortgage and equipment payments due now? Why care about the valuable ecosystem services, when all Pepsi, Nestle, Mondelez, and other food conglomerates want to purchase is raw calories for their ultra processed foods or confined animals?

You’d have to be a real stubborn fool to start a farm centered around trees.

Regular readers will know that I own and operate a permaculture farm, Blue Glade Farm, in my spare time. You can read our annual reports (2024, 2023, 2022) as well as our “master plan.” Our goal is to integrate the farm into the local ecological whole, while producing a diversity of nutritious food for ourselves and our community.

The foundation to the farm is a rotational chestnut-persimmon silvopasture system: animals living and rotating under tree crops, in this case, mainly chestnuts and persimmons. By the end of this spring, we will have ~80 chestnuts planted on our 12-acre farm. But as I mentioned above, the chestnuts planted this spring won’t start producing large harvests for another decade.

So today I’m launching the Adopt-a-Tree program at Blue Glade Farm, to help finance the transition period for one small farm. Everyone who subscribes to The Counterpoint with an annual or founding member subscription will be matched with a specific chestnut tree (or you may select another tree species, we have many).

Now, I have never asked The Internet for money, and I feel a bit strange doing it. But I want to assure you that this isn’t begging; you’ll receive several things in return.

details on your tree along with an annual update picture

several pounds of chestnuts from your specific tree (this will be a handful of years from now, but I’ll keep in contact via the annual updates). Alternatively, if you select a fruit species, see the footnote.2

a free tour of Blue Glade Farm, should you ever visit

the knowledge that you’re directly supporting a small farm and family that is actively trying to enhance their land and community through stewardship

a subscription to The Counterpoint

More on that last point: One of the metagames that I’m playing with my life is that the more income that my side projects (the farm and this newsletter) generate, the sooner I can “retire.” But once I’m no longer dedicating 40+ hours of my week as a biomedical engineer, I can dedicate that time to making the farm and the newsletter even better.3

That isn’t to say that I think they’re not worth it now! Obviously, I am biased, but I think The Counterpoint is interesting, thoughtful, wide-ranging, and worthy of subscription. This is merely an attempt to hook you into this newsletter by tempting you with delicious chestnuts plus the knowledge that you’re directly supporting a small farm and family.

If this is your first time reading, I’ll link to the pieces I’ve written so far in 2025 plus several of my favorites from previous years:

2025 Counterpoints:

Becoming a father is the best thing I’ve ever done, often in some surprising ways.

Some predictions about the second Trump presidency, to be reviewed after the midterms and next presidential election.

Meandering thoughts about G.K. Chesterton, modernity, and AI.

Older Counterpoints:

Attempting to find value in the oft-maligned “degrowth” movement.

How a cathedral in Venice explains an ultra-rare genetic disease.

Reflections on modernity, civilizational development, and where we should go from here.

Perhaps my hottest take ever, sure to infuriate every side of the political aisle.

And it all goes back to Richard Nixon.

I should and plan to write more about it here. I’ve kept most of it siloed on Twitter, but trust me, more about agriculture is coming to The Counterpoint.

I can’t really send fruit through the mail, so if you decide to adopt a pawpaw or persimmon tree, you’ll have to forgo this benefit. However, if you’re local/ever visit, we can rectify this then.

One amusing aspect of this is that you might think my utility is maximized as a biomedical engineer, creating a disincentive to subscribe here or purchase my farm’s products. And I can respect that, as I agree that cancer and autoimmune diseases (where I spend most of my current scientific career) are awful diseases that we should dedicate more resources to solving.